hol In the fifth and final chapter of this saga we go deep inside the back room negotiations to release Bergdahl and the controversy that would await him after his release.

In the fifth and final chapter of this saga we go deep inside the back room negotiations to release Bergdahl and the controversy that would await him after his release.

by Robert Young Pelton

By late 2013 Bowe Bergdahl had been a prisoner of the Haqqani’s in Pakistan for almost half a decade. According to Bergdahl’s account, he fought back , he refused to convert, refused to eat cooked food (an insult to Pashtuns) and he refused to bathe. He escaped multiple times ending up in a small cage. Like most of his decisions, he ended up choosing the one that would make it harder on him.

Bergdahl had no idea how to deal with being a hostage in a region where kidnapping was perfected as part of the culture. Just in-country and eager to understand the strange land he quickly began to dislike his commander and in June 2009 he left his small group of 33 soldiers to walk 30 kilometers north to the unit’s headquarters and file an official report on his unit. The naive US soldier was quickly kidnapped and after some clumsy attempts by tribesmen to trade him to the base commander he was hustled over the border to Pakistan. My previous chapters 1, 2, 3 and 4 were published in Vice to detail this extraordinary event. I chose to ignore Bergdah and let him tell his own story. My focus was learning from the insiders who tried to help, and sometimes hinder, his torturous path to freedom. Bowe Bergdahl has now told part of his story in a bizarre Hollywood discussion with a producer and again through a detailed video interview with former hostage Sean Langan but his story is only beginning to be told.

The story of Bergdahl and the efforts to free him also are tossed in an ocean of angry condemnation, biased news reports, slanted commentary and stern accusations from five years of speculation on Bowe Bergdahl’s motives and that is then whipped up into a by a storm of personal agendas that sunk any chances of Bergdahl had of ever being understood calmly and fairly.

OVER THE LINE

The negotiations leading to his release on May 31, 2014 had come a long way from the first hours of his kidnap after June 30, 2009. Or even a few days later when U.S. Army Major Crapo unsuccessfully offered local Taliban leaders boxed MRE’s and some basic supplies in exchange for the missing soldier. The tribal leaders said they had Bergdahl and wanted to deliver him back to U.S. forces. The Major was not eager or able to negotiate that rapidly on behalf of the U.S. military so the locals then promptly sold Bergdahl to the Haqqani Network. The Haqqani’s were members of the Zadran tribe who had moved across the Durand line in a political spat in the 70’s. They grew to become a formidable transnational organization who had made kidnapping a profitable business and political tool. However they had just lost New York Times’ reporter David Rohde after his escape from Miram Shah. Rohde’s captors had been enticed (or drugged depending on which source telling the story) to allow Rohde and his interpreter to climb over a steep wall and run to safety. That left Siraj Haqqani, the young military leader of the Haqqani’s without his best bargaining chip to free prisoners held in secret prisons in Afghanistan along with having to explain to his ailing father Jallaudin, why they lost a chunk of cash.

Bergdahl’s captors spent five years being shifted him among a series of makeshift prisons in the semiautonomous tribal areas in Pakistan just 30 kilometers across the border from the Observation Post called Mest Malak where then 23 year old soldier from Hailey, Idaho first disappeared. False intel reports provided by the intelligence network originally cobbled together by the “New York Times” to rescue Rohde but soon contracted to the military described a Bergdahl who had converted to islam and carried a gun. Dewey Clarridge the former CIA anti terrorism had transformed the KRE insurance-funded rescue gig into a intel network looking for money from the U.S military in Afghanistan. He managed to get $6 million but when that ran out he fired off numerous and random intel briefs, among them extremely damaging and unvetted stories of Bergdahl’s duplicity. The truth was very different. Bergdahl took pride in his outdoor and survival skills. He tried to escape his captors a number of times. Each time he was caught by locals brought back and punished.

Bergdahl was been beaten with chains, cables, hoses and sticks. For a large part of his captivity he was kept in a welded together 6′ X 8’cage, chained to a bed, hit with sticks, had his food spat in, suffered constant gastric pain and diarrhea and had escaped again and again to be returned and treated even more savagely.

He had appeared in seven videos during that time, including one in which both his physical and mental condition had deteriorated significantly in his captivity since the first video was released that observers thought he was near death. In July 2009. Looking frail and shaky during the May 2011 footage, Bergdahl mumbles a heavy-handed rant about how the Afghan war wastes lives. Then he wanly says, “Let me go. Get me to be released.”

A Pentagon spokesperson responded to the video: “Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl has been gone far too long, and we continue to call for and work toward his safe and immediate release. We cannot discuss all the details of our efforts, but there should be no doubt that on a daily basis—using our military, intelligence, and diplomatic tools—we work to see Sgt. Bergdahl returned home safely.” Bergdahl survived on that hope.

To a large part of America, Bergdahl was a traitor who fled to join the Taliban, to others he was a victim, someone snatched at night and hidden in a cruel place. To some Bergdahl deserved his captivity, to others his safe return as a U.S. soldier was paramount. There would be time for him to explain what happened but a constant flow of stories many of them pure invention would not let him ever live down a reputation the media foisted on him.

In the long running war on terror, Americans felt little pity for Bergdhal. They also had no time or space to think of the Afghans that had been kidnapped and hidden in cruel places. One part of the story was completely missing from the history books but buried in Gitmo records and first hand experiences. For the first time a kidnapped American soldier and kidnapped Afghans who were working with American soldiers would be swapped, creating another bizarre an unexpected firestorm of protest from the American public.

THE PET MULLAHS

Mullah Faisal, former head of the Taliban Army in the North on operations with General Dostum and U.S. Special Forces © Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved.

In late 2001 I had met and stayed with two of the Mullahs who would later be swapped for Bergdahl. They had just surrendered to the Northern Alliance and General Dostum in a quasi formal ceremony held at the 19th century garrison of Qali Jangi near Mazar-i-Sharif. They had offered to convince the remaining taliban to lay down their arms and give up the foreigners hidden among them.

Mullah Faisal, the head of the Taliban military in the north and Mullah Nuri the Governor of the region were both prisoners under house arrest but eager to put the war behind them.

Aided by his own personal U.S. Special Forces team, Operational Detachment Alpha 595, Dostum was eager to finally return peace to the North. His ouster by the Taliban and long exile in Turkey made the victory an emotional event. After the murder of General Achmed Shah Massound by Tunisians posing as journalists just before 9/11, I had the good fortune of being trusted and invited by Dostum to document the war without restriction. I knew from my time with the talion a few years earlier that part of bringing peace in Afghanistan requires forgiving your enemy and move on. The taliban had violated this when they invaded the north and murdered thousands of shia Hazara and other Afghans. Despite this duplicity (and a number of false surrenders that killed some of Dostum’s commanders) he was willing to show that peace with the taliban was possible.

Dostum was eager for me to meet his trophy mullahs, fellow house guests kept adjacent to his compound. Dostum treated the two morose leaders and their entourage more like honored guests than prisoners despite their driving him into exile in Turkey in May of 1997. Back then in a stunning betrayal by one of his commanders. the Taliban swept into Dostum-controlled Mazar I Sharif and began slaughtering thousands of Hazara Shias. When I asked to film and interview the mullahs, they were not happy. The old school Taliban had vandalized all the faces in the paintings in Dostum’s house and smashed all the televisions. They agreed to my interview requests. They sat glaring at me, wrapped against the November cold in brown wool blankets. Faisal, who had removed his prosthetic leg was a perfect caricature of a talib commander, he had pitted skin, bad teeth, and just glared. Mullah Nuri also had the black serious scowl of an angry Pashtun but was chattier than Faisal. Their message? “That the Taliban movement over and they hoped the Afghans would not be too tough on them.”

To prove that they wanted to put the last 6 years of brutal fighting behind them, the mullahs went with Dostum’s men and the SF team on military missions in their gold Land Cruiser. While I filmed Dostum and his US Special Forces team surround Pashtun pockets to oust stragglers the mullahs would helped seal peace deals. It was clear that the allegiance of the Pashtuns in these pockets created by the same builder of Qali Jangi was based more on survival than beliefs. But for now the pragmatic approach of negotiations with the underlying repercussions of extreme violence worked. The Pet Mullahs (as I called them) were the trump card played to show the local taliban that given a choice between a B 52 strike and living like our new best friends, the mullahs, the decision was easy.

Then one night, despite their eager alliance with the US, on someone’s orders, the Mullahs were roughly awakened, stripped, bound with cargo strapping, sedated anally, blindfolded with cotton behind welder’s goggles and flown by military aircraft to an offshore hospital ship until Gitmo opened up. There were among the first prisoners there and were never charged with any crime. Although in early 2002 this would be perceived as revengeful and just it set the tone for the decade plus long war that was to follow. A rapid number of Afghans who were working with the Agency and the DIA also were roughly hogtied and vanished into the unknown.

The warnings of Mullah Daddulah, the other one legged hold out mullah, to the one legged Faisal not trust the Americans and their allies rang true and the Taliban insurgency began.

FAILED RANSOMS AND RESCUES

March 10, 2012. A U.S. Army PR photo shows 1st Platoon, Company A, 1st Battalion, 2nd Infantry Regiment, Task Force Black Hawk, conducting a foot patrol in Yayah Khel, where Bergdahl vanished from years earlier.

During my research I discovered that finding Bowe Bergdahl launched two failed rescue missions, two failed ransom payments, and finally a successful financial negotiation and complete capitulation to the Haqqani’s, his kidnappers’ and the Taliban’s demands. Politically America under President Obama had run out of options to end the war and breakthrough solution that bypassed the Pakistanis was needed.

The Taliban were equally desperate. Unbeknownst to the world their leader Mullah Omar had died in 2013, setting off uncertainty and succession squabbles. The Taliban were able to fool the Germans and the U.S. into negotiations on his behalf even though the one eyed Mullah had been dead for a year after Bergdahl’s release. This resulted in the most lopsided and contentious prisoner exchange in American history. Overshadowing perhaps the Iran-Contra affair in the 80s that traded Israeli-brokered weapons as collateral for the return of US embassy staff kidnapped by Fedayeen revolutionaries in the wake of the Iranian Revolution and overthrow of the Shah.

The contentious release also wrong footed the White House and exposed a history of other negations to free Bergdahl. One in specific that required no ransom and would have released other hostages held by the Haqanis’.

The follow up resulted in an ugly attack on Special Forces war hero Lt Col Jason Amerine who was among the first on the ground after 9/11 and after negotiating a deal to release all hostages held in Pakistan, was ignored and shocked at the incompetence, infighting and bungling of how America searches for their captives. When he finally spoke out to Rep Duncan Hunter and sought whistleblower protection, the FBI maliciously charged him with leaking secrets, stopping his paycheck, retirement and attempted to punish a man who worked tirelessly to get Bergdahl home.

When Bergdahl returned there was wave after wave of controversy as Bergdahl himself stoked the controversy. A failed film deal turned into a podcast, a TV interview tell all that slammed his accusers and the decision to plead guilty without a plea bargain would all shock followers and simply continue his demonization.

THE PAWN

It is now known that the US had made halting attempts to broker a peace deal shortly before Bergdahl was kidnapped in June of 2009. During the Bush administration, the US had opposed any reconciliation with the Taliban, despite Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s support of such a move. The American view was that Talibs should switch sides and pledge allegiance to the new Afghan government, as if it were a binary decision. The multipronged alliances of Afghans seemed invisible to their Western friends, even though American officers had studied their jihad against the Soviets, which was successful in part due to complex, shifting alliances. Instead, American officials had a dismissive, simplistic expression: You can’t buy an Afghan; you can only rent one.

Not long after taking office in January 2009, President Obama reversed the previous administration’s strategy and ordered a two-month policy review. “In a country with extreme poverty that has been at war for decades,” Obama said in March 2009, “there will also be no peace without reconciliation among former enemies.”

Karzai welcomed the change, citing reconciliation as the most significant aspect of a plan that also included military aid and money for development. Pakistan’s president, Asif Ali Zardari, also oversaw the appropriate approvals, perhaps motivated by his country’s cut—$1.5 billion per year in civilian aid for the next five years. The unspoken assumption in all this was that America could buy its way to peace—one elder, one village and one region at a time.

Ambassador Richard Holbrooke, Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan said he only have 90 days to “break the furniture”. His attempt to work back channels to free Bergdahl created a complex deal in which Talib mullahs in Gitmo would be traded for Bergdahl.

To jumpstart the process, Obama deputized veteran diplomat Richard Holbrooke as the special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan. In June 2009, just a few weeks prior to Bergdahl’s capture, Holbrooke’s road to peace in Central Asia took him to the tiny kingdom of Qatar.

Ambassador Holbrooke had an audience with Emir Tanim bin Hamad al-Thani, the UK-educated crown prince of Qatar, to discuss, among other things, how the prince could help with Afghanistan and Pakistan. For years Qatar (which has a population of two million, an eighth of whom hold Qatari passports) had volunteered to insert itself into regional disputes as an open-minded deal broker that worked “the full spectrum of ideologies.” While al-Thani would usually send a deputy to handle such matter, he had agreed to meet with Holbrooke to discuss the rift the war had created between the unpopular Afghan government that had been installed vis-à-vis the equally unpopular but ascendant Taliban. The fates of Afghanistan and Pakistan were—and still are—inextricably intertwined, partially because the latter belongs to Club Nuclear. As Holbrooke succinctly put it: “America could tolerate an unstable Afghanistan but not an unstable Pakistan.”

While the Americans were discussing a potential mediator role with Qatar, the Germans were hosting casual meetings with self-described ”former” Taliban officials in Dubai, just 200 miles east of Qatar. Germany might seem like an odd participant in Afghan affairs. The country, however, has historic ties to Kabul and has hosted three conferences to assist post-war Afghanistan. This included the Bonn Conference in December 2001, which brought the relatively unknown Hamid Karzai to power following UN-supervised power-sharing negotiations.

In 2010, an Afghan-German had told Bernd Mützelburg, Germany’s special envoy to Afghanistan and Pakistan, that he could introduce Mützelburg to Syed Tayyab Agha, a wispy-bearded, 35-year-old who appeared to function as the chief of staff for Mullah Omar, the Taliban’s reclusive leader living in exile in Quetta, Pakistan. The Afghan-German individual suggested that Agha could function as the interlocutor between the US and the Taliban.

Agha appeared to have all the basic Taliban bona fides: He wore the black turban of the talib, and a bulky olive-green military greatcoat favored by the organization. Born in 1976 in Kandahar’s Arghendab district, he was a member of the Popolzai tribe, as was Karzai and the deposed Afghan monarch, King Zahir Shah. His father had been one of Mullah Omar’s religious instructors in Kandahar, and his older brother, Lala Malang, had been a well-known jihad commander during the Soviet occupation. Agha spent most of that era as a refugee in Quetta, studying the Quran and foreign languages, including Pashto, Dari, Urdu, and English. Afgha was not a diplomat, a lawyer, or even man of means. His major skill in the retro-rural Taliban organization seemed to be his ability to use a computer.

Beginning in November, 2010, a series of eight meetings hosted in Bavaria, Germany, as well as in the Persian Gulf, took place between the Germans and Agha before Berlin had established enough trust for the US to step in. As a guarantee to their safety, the Talib present at the meetings insisted that a member of the Qatari royal family was present since the US had a habit of luring, and then arresting, members of the Pashtun rebel group on the grounds of supposed negotiations as they had in early 2002 with the Mullahs who were later to be released for Bergdahl.

The prime example of American duplicity was rotting away within Guantánamo Bay: five senior Taliban members languishing in perpetuity at GTMO. Before their prison-camp sentence, all the Mullahs and Afghans slated to be swapped for Bergdahl had all worked with the CIA or US-designated elements in the immediate post-9/11 Afghanistan. Thinking that the US was willing to talk peace Afghan style in which commanders and leaders simply swap sides in exchange for amnesty and nice living salary, the mullahs were surprised when American operatives suddenly captured them and packed them off to Navy ships, eventually dumping them in Gitmo.

In 2010 any meetings with the Taliban had to be secret. Very secret. If rank-and-file, fight-to-the-death Talibs in Afghanistan knew that the Quetta Shura, the Taliban government-in-exile in Pakistan under Mullah Omar, was negotiating with the infidel invaders it would severely undermine the insurgency movement. As for the U.S., peace talks seemed like a very thin olive branch compared to the big stick of the surge. After the 2001 surrender, the double cross and a decade of shifting goals and fortunes, peace talks seemed like a waste of time. The mood in both camps was not conducive to giving anything away. But Bergdahl changed all that when he was offered as a swap for numerous Talib prisoners.

An insider at the peace talks between the Taliban and the US (Led by then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton) recalled to me: “[The Taliban] knew they couldn’t come into the political system by suicide bombing their way to the presidency.” There were two ways they could transition into a legitimate political party, much as Afghanistan’s ethnic militias of the 1990s had done. “They had to renounce terrorism,” the insider said, “and they had to give back our guy.”

Senator Obama makes a pre election trip to Afghanistan. This was a war he said must be fought but after the failure of Petraeus’ “surge”, of which Bergdahl was a part of, reversed his strategy and began to look for a way out. Suddenly Bergdahl become a bargaining chip to close down Gitmo and bring the Taliban to peace talks.

“Our guy” meaning Bowe Bergdahl. Somehow America’s foreign policy in Afghanistan suddenly shifted from a complex but featureless geopolitical framework to the safe return of a singular hostage who had wandered off his post on some misguided quest.

The first formal meeting to set the stage for peace talks occurred on November 28, 2010. A 19-passenger Falcon jet operated by the German foreign intelligence agency, the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), was dispatched to the Persian Gulf to pick up Agha and two associates, rumored to be the former Taliban ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Mualavi Shahabadin Delawar, and the former Taliban health minister, Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai. The BDN flew Team Taliban to Munich, Bavaria, where the Talibs were whisked through customs and immigration, and then driven to Mützelburg’s home in a nearby village for a meeting that lasted more than 11 hours.

The peace talks were a microcosm of the military campaign. The US had sent seasoned diplomats, including Holbrooke’s deputy, Frank Ruggiero, and Defense Intelligence Agency staffer Jeff W. Hayes, a former First Group Special Forces soldier and expert on Afghanistan and Pakistan. It is likely that the Qatari representative was HBJ, the country’s high rolling Prime Minister Hamad bin Jasim al-Thani. Although Sheik Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani was the ruler of Qatar he insisted that Hamad owned the country. The ruler of Qatar had been born in a tent but with his scheming Prime Minister had taken over control in a coup and were busy creating a powerhouse either by using al Jazeera or brokering deals. Their support for Hamas, the Egyptian Brotherhood or even supporting the downfall of Qaddafi and their vast cash resources made them important middlemen.

It was important that the Americans not physically meet in the same room as the Taliban so that the U.S government could say with a straight face that they were not negotiating with the Taliban.

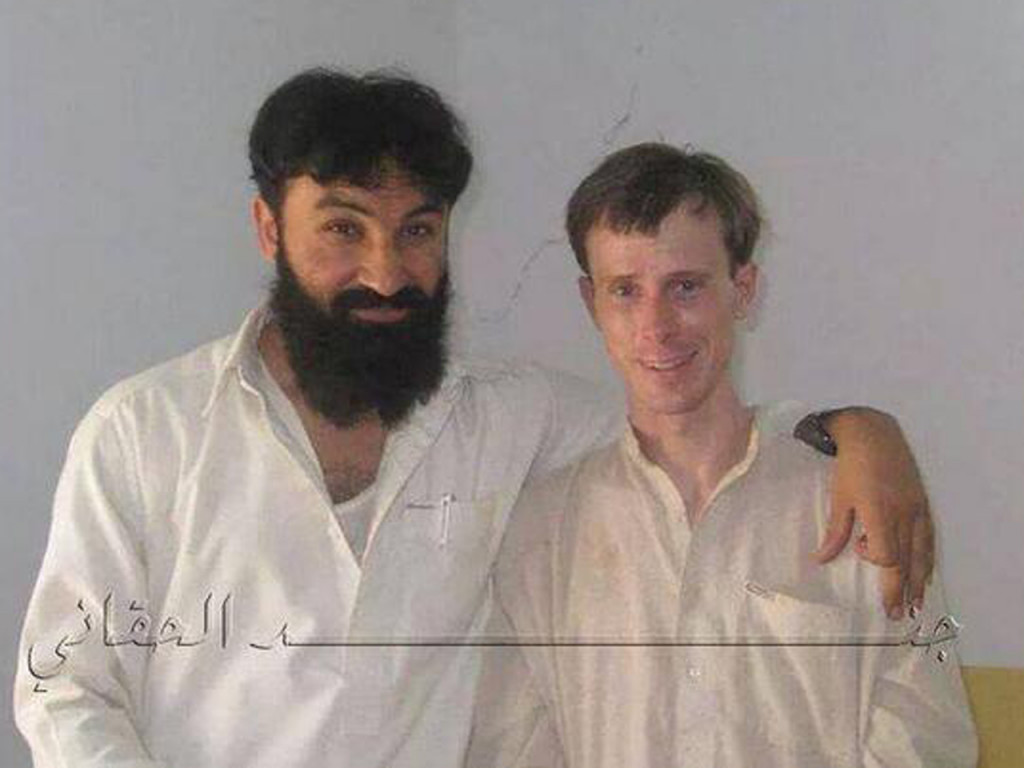

Siraj Haqqani posing with Bowe Bergdahl was part of an clumsy but effective PR campaign to keep the pressure on the U.S. to negotiate a deal. Bergdahl was dressed in various outfit and told to recite various speeches to garner media attention.

The Taliban delegation consisted of the badly dressed Agha and two associates.

The idea of well-heeled, educated US diplomats interfacing in a posh European home with the backward Taliban seemed more like the premise of a Monty Python comedy sketch than a global diplomacy. The question during this first set of meetings was did this ragged Taliban trio really have the authority to speak for Mullah Omar and the Quetta Jura? Or was Agha just another country bumpkin looking to wiggle his way in the middle of a lucrative hostage exchange and political boondoggle?

Early results were promising, however, and Holbrooke, who had trouble remembering the Taliban negotiator’s complicated name, soon began calling him “A-Rod,” after the New York Yankees slugger. According to the insider, the talks initially revolved around a general peace deal, but quickly morphed into a more targeted and narrow objective: Swapping the only American POW in Pakistan for some of the Taliban POWs in Cuba. More specifically, Bergdahl for the GTMO Five—Mullah Mohammad Faizal, Mullah Norullah Nuri, Khair Ulla Said Wali Khairkhwa, Abdul Haq Wasiq, and Mohammad Nabi Omari. These senior members of the Taliban had been in Cuba since 2002, and for years their organization had been calling for their release.

The Haqqanis, who kidnapped victims strictly for ransom, had introduced the concept of a classic Afghan prisoner swap. They wanted a long list of Pakistani and Afghan prisoners for captured New York Times journalist David Rohde in November 2008. Rohde’s kidnappers had complicated things when they demanded cash and naively, the release of Taliban prisoners from both GTMO and Bagram. And at some point a female Pakistani nuclear scientist held in the U.S. was added to the list. Clear indication that the Pakistani ISI had some chips on the table. According to the insider who spoke to me on the condition of anonymity, “It was a big disaster for David Rohde’s people, thinking the US would exchange prisoners [for Rohde].” It would be difficult enough trying to raise ransom money secretly; adding a complex prisoner exchange to the deal made the release of Rohde seem virtually impossible. In the end despite efforts to both launch a rescue attempt and pay a million dollars in insurance money, Rohde escaped on June 19, 2009. Less than two weeks later, the Haqqanis landed an even more valuable American hostage: Bowe Bergdahl.

According to the insider, the prisoner-swap deal point “was when the efforts [to start peace talks] became cross-pollinated and contaminated by characters carrying messages.” A large-scale nationwide reconciliation process was being reduced to a Mexican standoff in which each side forgot about the good of the Afghan people and instead focused on its own political self-interests. Mullah Omar needed to assuage his hardline supporters and the friends of the so-called Taliban Five; Obama could not be seen as a weak leader who simply handed over prisoners in the War on Terror and received nothing in exchange. Mullah Omar could not be seen as being two faced. Demanding that Afghans die to oust the infidel, but cutting deals that would allow his inner circle lodged in Karachi Pakistan to escape the hardship of jihad.

On February 15, 2011, the US and the Taliban held another secret meeting in Qatar’s capital of Doha, to move the peace talks and prisoner swap along. Just three days later, at an Asia Society event in New York to honor Holbrooke, who had died unexpectedly in December, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton undermined the negotiations by giving a major speech denouncing the Taliban as “an enemy of the international community.” The left hand was having a hard time knowing what the right hand was doing.

By the spring of 2011, the best deal the Americans could come up was to release what they deemed to be the three least important members of the Taliban Five and wait 60 days to see what impact it had on the U.S media and ultimately voters. If there were no major political repercussions, then Bergdahl would go free and the US would quietly release the other two mullahs. If both sides felt confident in one another, then they would move toward integrating the Taliban into an Afghan political structure. Few Americans knew who was being held in Gitmo let alone where it was. None knew how exactly how many Afghans were being held in Afghanistan and black sites around the world.

To show the Taliban that its offer was in earnest, the US got busy working to remove former Talibs from the United Nations sanctions list. The UN can lock up a group or person’s travel freedoms and money worldwide with a stroke of a pen. It sounds humorous but some of the Talibs could not fly because of the ban. It also not coincidently meant that money could not be sent to certain Taliban. Luckily both parties were able to work out a swap, the US could ship the five Taliban prisoners from GTMO to Qatar without running afoul of UN Resolution 1267, which (in part) banned international travel of Taliban who served in the Afghan government in the late 1990s. By the end of the year, the UN had removed or amended 105 names on the sanctions list.

THE PHANTOM

Then came May 2011, a month filled with violent actions and consequences. On May 2, a US Navy SEAL team assassinated Osama bin Laden in a featureless compound in rural Pakistan, where the al Qaeda founder had been living for five years, only a few blocks from a major military installation. The incursion by US forces into an ally’s sovereign territory plunged potential cooperation with Pakistan on peace negotiations regarding Afghanistan into the deep freeze. Technically the Taliban were Afghan but they, like the Haqqanis, and Bergdahl were based in Pakistan. Theoretically Pakistan was an ally of the U.S and Afghanistan but had long played all sides against the middle.

Two days later, on May 5, the Haqqani Network released its fifth video of Bergdahl. The clip shows the haggard and battered prisoner and a laughing Mullah Sangeen, a commander from the Zadran tribe. Sangeen blindfolds his American captive and leads him away from the camera’s view. The jocular tape was shot prior to the death of bin Laden, who had begun his jihadist career in the early 1980s as a volunteer with the Haqqani Network. The video had little impact in the US but if there was no confusion that Pakistan was harboring Bergdahl’s kidnappers.

Three days later, on May 7, the US and the Taliban held a third meeting on the outskirts of Munich. It was chaired by Michael Steiner, the new German special representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan, with Qatari Prince Faizel al Thani present as a guarantor of the Talibs’ safety. Given the timeline, the main topic of discussion was most likely not the most recent release of a proof-of-life video of the American soldier, but rather the assassination of the a dour tall Saudi exile, Mullah Omar and the Taliban’s most vocal and visible supporter.

August brought a fourth meeting, this time in Doha and this time the agenda at hand largely reverted back to Bergdahl. Agha presented Ruggiero a personal letter from Mullah Omar addressed to President Obama. In it, Mullah Omar encouraged Obama to speed things up regarding the potential prisoner swap. Soon after this the two sides agreed that the Taliban should proceed with setting up an office in Doha to be staffed by a couple dozen Talibs. Then, of course, the US made this very simple deal very complicated. If freed in exchange for Bergdahl, the men who would come to be known as the Taliban Five would have to stay in Qatar and be monitored around the clock until an overarching peace deal was struck in Afghanistan.

Despite Mullah Omar’s letter and the US’s caveat for the swap, the Americans continued to move at a glacial pace. “By summer 2011, we were in listening mode,” the insider told me. One fundamental stumbling block: The Americans still weren’t convinced beyond a reasonable doubt that Agha spoke for the Quetta Shura let alone Mullah Omar. There was doubt whether the newer rebel group, the Taliban truly had the authority to order the much older and powerful Haqqani Network who had shifted away from their former US Reagan-era support pledged support to Taliban in 1995 . And then there was Pakistan. The Americans asked Agha to provide yet another proof-of-life Bergdahl video. He did. Whatever was on that video, which was classified and never released to the public, helped convince American officials that Agha was a legitimate proxy for the Taliban’s leadership.

But the Taliban were also cautiously biding their time, but for much different reasons. They knew that if their fighters became aware that Mullah Omar was sending out peace feelers, morale and support for their cause would be dramatically undermined. The Talibs (and just about everyone else in the world) were also baffled that it was taking years to make good on the Obama’s 2008 election promise to shut GTMO for good. Despite the President of the United States making multiple public promises to shut the legally gray holding pens, some key US officials were not about to release battlefield detainees without a fight. James Clapper, then the director of national intelligence, and Leon Panetta, director of the CIA, objected to a potential prisoner swap with an insistence that the Taliban prisoners were too dangerous to release. When the insider who spoke me with me suggested to military officials that releasing the GTMO Five would be a step forward in the peace process, his military counterparts not only balked at the suggestion but became aggressive in their response. The insider recalled: “I thought they were going to send me to Guantanamo.”

By August 2011 progress was being blocked stateside then Afghan President, and former Pakistani resident, Hamid Karzai and his government were miffed at being left on the sidelines, out of the action. Their strategy was to leak the details of the talks including dates, locations, and the identity of the Taliban’s envoy. The State Department and the Pentagon were forced to confirm these talks. Not surprisingly, the Taliban pulled out and months of clandestine work went down the toilet. Pakistan had apparently restored the status quo.

Karzai, ever the opportunist, tried to shift the negotiations to his own reconciliation vehicle, the High Peace Council, which he had created in 2010 and packed with doddering elder Soviet-era jihadi turned statesmen. At the time the council’s leader was Burhanuddin Rabbani, a multilingual Tajik cleric who was the president of Afghanistan during the mujahedeen years until the Taliban ousted him in 1996.

THE BOMBS

“Smart Bombs” from above and smart bombs from below. Targeted suicide bombers from Haqqani and the CIA drones became the favored kinetic weapons in the Pakistan tribal areas and Afghanistan.

On September 20, 2011, Rabbani had just returned from a trip to Iran and was receiving visitors at his Kabul home in honor of his 71st birthday. A man named Esmatullah had been staying at his guesthouse, where he had been waiting for the elder Tajik cleric. He talked his way in with the claim that he was an important Talib commander who wanted to talk peace with the council leader. When the two men finally met, Esmatullah bowed low and detonated a bomb in his turban, killing himself, Rabbani, and two other council members.

To ensure that there was enough bad blood to smear everyone involved, the US Special Operations stepped up their pressure on what was called the Haqqani Network. The organization is affiliated with the Afghan Taliban but operates autonomously, mostly in eastern Afghanistan with its main base located in North Waziristan. Maulwi Jallaluddin Haqqani, an ethnic Pashtun from the Zadran tribe in Khost left Afghanistan in the late 70’s after leading an uprising against Daoud and an important cross border organization. With his border ties, was an important CIA-financed freedom fighter during the Soviet occupation, with close ties to the Pakistani spy agency Interservices Intelligence (ISI). After Jallaluddin suffered a stroke in 2005, he tapped his eldest son, Sirajuddin, to take over the organization. Haji Mali Khan, who is Sirajuddin’s uncle, was described as the brains of the operation—paying bills, setting up safe houses, and planning operations like the one that had killed Rabbani. Financing for the organization reputedly originates from Arab donors in the Persian Gulf, the extortion of legitimate businesses, smuggling, protection rackets, and, most prominently, the bread-and-butter of kidnapping and ransom.

A few days after Rabbani’s assassination, a US Special Operations team kidnapped Haji Mali Khan in the Musakhel district of Khost province. Khan was the highest value Haqqani target the US had ever captured. A month later, in November, the US officially labeled him a terrorist. Khan then disappeared into the bowels of the CIA’s secret detainment and interrogation system. He has not been seen or heard from since, and his name does not appear on any US prisoner list. It would appear that the primary goal of capturing Khan was to change the dynamics in negotiations for Bergdahl. If that was the case, the plan failed miserably. Although Khan was captured with great media fanfare, the same media is silent on his current whereabouts.

Certain US officials may have balked at releasing prisoners from GTMO, but they had no qualms about clearing out overcrowded detention centers in Afghanistan. Thousands of detainees captured during the surge and during better intelligence were clogging the system. All of them awaiting charges to be pressed by Afghan prosecutors or simply being held. The conditions in some of these CIA-run facilities with names like the “Salt Pit” were barbaric leading to the deaths of prisoners. In 2014 a U.S. report detailed stories of freezing naked prisoners, shackled to steel bars, kept in cages and subjected to carefully designed abuse. Bergdahl would have understood the conditions well, as would the Haqqainis whose provided a list of Afghans they wanted released from these prisons.

In March 2012, the US in an attempt to show good faith and the growing authority of the weak Karzai government transferred control of the largest single group of Taliban prisoners to Afghan officials. Instead of prosecuting them, as the U.S. expected after a review by US military lawyers, the Karzai-appointed judges simply let them all go, citing a lack of evidence. The basic drill: As long as the detainees—who were being held without charges—promised to renounce violence, they could go home. The same terms agreed to by the Taliban who surrendered to General Dostum in late 2001. While controversy stormed over what to do with the few hundred captured prisoners in Gitmo, over 3,000 detainees flowed out of similar, US-run facilities like Parwan on the Bagram Airfield, north of Kabul. The number of captured Taliban fighters flowing back out into Afghan society dwarfed the total number of men ever held inside Guantanamo, let alone released.

In 2012, the once hopeful negotiations with the Talibs to release Bergdahl devolved into a Gordian Knot. To show good faith on the U.S. side, the Taliban wanted their prisoners released from Gitmo and to show earnest movement on the Taliban side, the U.S. wanted Bergdahl back. Things may have been confusing in Afghanistan and Pakistan but the real fighting was inside the American government. became increasingly clear that there was dissonance between the State Department and the Department of Defense on the plan to get Bergdahl back. To make things more complicated, the FBI insisted that Bergdahl as a kidnapped American was their rice bowl. While the Americans squabbled and stalled, an opportunity arose to work the dysfunction between the Haqqanis and the Taliban.

THE RANSOM, TAKE ONE

In Afghanistan, shuras, negotiations and self interest were the tools in resolving conflict, hostages and resolution. But in a desperately poor region, cash is the best shortcut. © Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

That same year, 2012, an Irish academic named Michael Semple (Michael was contacted for this article and did not respond) began working on a more straightforward approach. Semple had worked on my AfPax project and had deep cultural roots among the Pashtun (he is a fluent speaker) and unique understanding of the Afghan and Pakistani landscape. Our job was to not only help the U.S. military understand what was happening on the ground but to explain what wasn’t happening and why. The CIA and State Department had deliberately sidelined and “PNG”d some major power players in an effort to let Karzai flow in his cronies. Karzai’s appointees knew they were not welcome and began lining their pockets, creating perfect entrée’s for the Taliban. Eventually AfPax set up secret meetings between Taliban commanders and one Star Generals in Italian restaurants and ostracized warlords to frame major peace deals. Semple was a key part of dealing with the Taliban.

Semple’s idea to free Bergdahl was simple: Pay the Haqqanis a $10 million ransom and cut the Taliban out of the deal. There was only minor wrinkle, the Haqqanis became a terrorist group in September of that year. The Taliban weren’t. Semple is a visiting research professor at the Institute for the Study of Conflict Transformation and Social Justice at Queen’s University Belfast, and a Pashto-speaking expert on the Taliban. Semple’s logic from a source, was that for three years the Americans and the Taliban had talked about the prisoner swap, and nothing had happened. So, he figured, why not deal directly with the Haqqanis?

Semple’s access and insight to help numerous people who were forced to deal with kidnappings in Afghanistan included assisting the wife of David Rohde. The New York Times reporter had been held by the Haqqanis before Bergdahl’s capture and his wife was concerned that his timely return being bungled. Rohde escaped or was rescued, before Semple could put the finishing touches on a ransom deal, but Semple’s approach was very simple: Cash is king. The Irishman has long been accustomed to the fear and the terror that the families of kidnap victims experience, and does not ask for payment for his services. He has never revealed who would provide the funds for his Bergdahl ransom scheme or if there ever was a final plan. Bowe’s father Bob Bergdhal is a retired UPS driver did not have the funds.

Semple’s correct conclusion was the Taliban Five had nothing to do with Bergdahl and that the mullahs would eventually be released from Gitmo. Additionally Semple personally knew four of the five Talibs from his days working for the UN in Afghanistan during the Taliban era, and considered them to be minor players. In his view, leverage their release for Bergdahl’s had unnecessarily complicated matters. And now things were a real mess.

Semple also believed that Mullah Omar had no real authority regarding the negotiations for Bergdahl, and that ultimately dealing with him would lead to a dead end. Actually Mullah Omar was dead.

For example ten days before Omar allegedly died in Pakistan April 3, 2013 an audio message from the Taliban leader ordered his commanders to stop kidnapping for ransom. “We need to understand that all those involved in this heinous crime were bringing bad name to the entire organization of Taliban,” Mullah Omar said in the recording. “We need to identify all those in our ranks. They need to be eliminated.” Mullah Omar had no authority because Mullah Omar was dead or to the more conspiratorial, he had been spirited away as part of a peace deal. According to the Taliban Mullah Omar died on April 23, 2013. Some say in a hospital in Pakistan, others say in Afghanistan. The Taliban insist they kept it a secret for two years, the U.S. government insist they never knew and Pakistan acted surprised. Rarely, if ever has a leader of a two decade long insurgency simply died without successors informing his minions. It was also on than exact same day President Obama was meeting with Hamad bin Khalifa al Thania.

The Haqqani’s became terrorists, making it illegal to transfer money for any reason. Semple dropped his plan to raise ransom money for Bergdahl. But, as we will see, some US officials believe and there is growing evidence that a significant ransom paid by the U.S. government ended up being part of the deal to free Bergdahl.

At the same time there were other U.S. hostages held in Afghanistan. USAID contractor Warren Weinstein was one of them. Weinstein had been kidnapped on August 13 2011 in Lahore Pakistan by eight men who were believed to members of al Qaeda. In 2012 the FBI, which usually takes the lead for all kidnapped hostage Americans “facilitated” a $250,000 ransom payment for the contractor. This is according to a source that worked directly with numerous agencies to free Bergdhal and other hostages. The payment never made it.

THE HIT LIST

On August 16, 2011, the US officially put Mullah Sangeen Zadran, Bergdahl’s minder who is seen joking about him in one of the hostage films, on the US terrorist list, which was the first piece of a framework intended to violently pressure the Haqqanis and pare down the plan to its simplest elements: Whoever is holding Bergdahl is going to die.

On September 7, 2012 Secretary of State Hillary Clinton applied pressure by very publicly labeling the Haqqani Network a terrorist organization. This also meant it was now illegal for the US to negotiate or pay off Bergdahl’s captors. It also meant that insurance companies and security corporations were not legally allowed to pay ransoms to the network for the release of kidnapped American citizens, thereby blocking any attempt by Bergdahl’s family to raise ransom money for their son. It would also ensure that go-between actors such as Qatar would think twice about providing a ransom on behalf of the US as a secret proxy for the Bergdahls. To make it worse, US agencies typically stonewalled or even threatened US families who thought they could pay a ransom to free their loved ones.

Back in the US, the presidential election was heating up, with political opponents and the media slamming Obama for not following through on his promise to shutter GTMO within one year of taking office in 2008. In October, President Obama appeared on “Comedy Central’s The Daily Show” to complain that Congress was blocking his attempts to clear out GTMO. “There are some things that we haven’t gotten done,” the president told Jon Stewart. “I still want to close Guantanamo, we haven’t been able to get that through congress.” He also (arguably disingenuously) explained that he needed a “legal architecture” before he could send prisoners home. Despite casting blame toward congress, earlier that year Obama had threatened to veto a bill from congress that would have allowed GTMO prisoners to be released. It was abundantly clear that while American families had sons and daughters fighting in Afghanistan, simply freeing Taliban prisoners seemed like a recipe for political disaster on all sides. In reality the US was having a hard time justifying the kidnapping and imprisonment of individuals for over decade without bringing charges against them.

After Obama was reelected in November 2012, the president’s team pushed to restart the peace talks. Obama wanted everyone to know his administration was ready to trade the Taliban Five for Bergdahl, even though the Taliban had consistently refused the American pre-conditions for a settlement: reject terrorism, end support of al Qaeda, and embrace the Afghan constitution. None of this really mattered to Bergdahl, who was now in year three of his captivity.

In late 2012, the Haqqanis moved Bergdahl from North Waziristan to South Waziristan, where the Mehsud tribe took over as his captors. US officials have a nickname for the Mehsuds: the “little t” Taliban, because they have been known to fight both the Pakistanis and the Americans, depending on their current predicament.

In February 2013, Obama proclaimed that the war in Afghanistan was effectively over. “This spring, our forces will move into a support role, while Afghan security forces take the lead,” the president said in his State of the Union address. “Tonight, I can announce that over the next year, another 34,000 American troops will come home from Afghanistan. This drawdown will continue and by the end of next year, our war in Afghanistan will be over.” Would Bergdahl be the last remaining American soldier left in the region?

In June, feeling optimistic that they would return home to some form of power-sharing arrangement in Afghanistan, and with the American need to remove Pakistan from the negotiations, the Taliban quietly established an official embassy of sorts in Doha. (Obama had privately agreed to the establishment of the safe house, using a Qatar businessman and member of the royal family as a cut-outs.) But, in fact, the setup wasn’t really a secret at all. The yellow-walled compound in the al Muather embassy district is only 300 feet from the US ambassador’s residence and was leaked by numerous media outlets. In addition, the US used one of its aircraft to fly in eight paunchy Taliban “diplomats” from Pakistan to staff their “embassy”. There were now two-dozen Talibs with full residency in Qatar, and when they finished shopping sprees, they returned to house #54, which they joyfully called the “Embassy of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan”. And really all one had to do was look up above the compound, where the white Talib flag the organization had used when ruling Afghanistan two decades earlier.

In a clumsy effort to rebrand the US and Qatari efforts as an Afghan-led effort, Karzai and newly appointed Secretary of State John Kerry, held a joint press conference before flying from Kabul to the new Taliban house in Qatar. Karzai insisted that the peace talks would soon move to Afghanistan. “We know the Taliban want to talk to us,” the Afghan leader smugly said. “They are already talking to the High Peace Council.” He was referring to a group of elders Karzai had created.

Obama supported the momentum of the peace talks, announcing that “Afghans” were talking in Doha in sync with the Afghan elections the following year. The public myth Obama was selling was that “… this was the first step in an Afghan-led peace deal.”

On June 19, the Taliban and Qatari officials held their first public press conference to announce the peace talks. The well-connected Sheikh Faisal bin Qassim al Thani had replaced HBJ as the Qatari go-between. Faisal al Thani’s public story was that he was a self-made man who started an auto-parts business in 1964 that had grown into a global empire of hotels, transportation, medicine, and foodstuffs. It didn’t hurt that he was the emir’s fifth cousin.

A month later, when Karzai returned to Qatar, he suddenly seemed very perturbed to see the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan nameplate on the wall of house #54 below the white Taliban flag. He theatrically demanded that the Taliban shut down their “embassy.” With this outburst, Karzai had effectively, once again, brought any forward momentum created to free Bergdahl and bring peace to the region, to a crashing halt.

On the home front, yet another round of negotiations concerning Bergdahl’s release, which was now inextricably and very publicly linked to the Taliban Five, was also starting to fall apart. Some Yemenis and Saudis who had been released from GTMO had begun to reappear on the battlefields of Afghanistan. This was excellent fodder for Republicans, who pointed out that Obama’s insistence on shuttering Camp X-Ray was another political misstep. The public mood was not forgiving.

The Republican-controlled Congress, which had spent almost half a decade making political hay from Obama’s inability to retrieve Bergdahl, now began to slap restrictions on the release of prisoners from GTMO. A Republican-sponsored addendum to the massive Pentagon budget bill moving slowly through congress required the President to seek congressional approval at least 30 days in advance for any transfer or release of prisoners from Guantanamo Bay. President Obama’s window to close Gitmo was being slammed shut

Congressman Jerry Nadler, D-NY, tried to add some logic and modifications to the restrictions on GTMO transfers: “At the end of the bill… insert the following: None of the funds made available in this Act may be used for the continued detention of any individual who is detained, as of the date of the enactment of this Act, by the United States at United States Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and who has been approved for release or transfer to a foreign country.”

Nadler’s logic was sound. If Obama was on a path to peace, what was America going to do with the 166 prisoners in GTMO, 86 of whom who had already been cleared for release? Would they just die in prison? The man who represented the constituency at Ground Zero insisted that detaining people without charge “… is against everything we claim to stand for. In response to this very situation of endlessly detaining people without pressing charges or holding a trial, President Obama asked: ‘Is this who we are?’ I hope today we will answer: No, we are better than that.”

The bill passed in July 2013.

THE DEAL

In 2013 a well known U.S. Army Special Forces Lt Colonel, named Jason Amerine was asked to look into the Bergdahl case. Amerine was famous because he was celebrated Captain of a team that worked with soon to be President, Hamid Karzai in 2001. His SF unit was awarded three Silver Stars, seven Bronze Stars and 11 Purple Hearts. They were also known as the unit that called in a airstrike on themselves. A mistake triggered by an order from a senior U.S. commander who wanted to bomb a cave, but ending up killing three Green Berets and wounding two dozen Afghans. A disaster that Amerine carries with him to this day. Amerine knew Afghanistan and he knew the major players. He was working on a DoD-sponsored deal that would free Bergdahl. He found that the Afghans were eager to resolve the other kidnap negotiations that had stalled as well. The Taliban were eager to do a deal not just Bergdahl but for Weinstein, Canadian Joshua Boyle, his American wife Caitlan Coleman and their children who had been born while they were hostages. According to Amerine there were two other hostages that were also part of the deal.

Amerine’s deal wasn’t complicated, he just knew that Haji Bashir Noorzai was a major player in the Taliban controlled south and that he was being held in a US jail on drug charges. Noorzai was also the man Mullah Omar put in charge when he fled Kandahar in late 2001. Coincidently the reason Omar had to flee to Pakistan was because of Jason Amerine coordinating coordinated 300 Afghan fighters and airstrikes. It all seemed very complicated unless you knew that the Haqqani’s and the Pakistan government controlled the destiny of all these hostages.

Amerine was also driven by survivors’ guilt. He had lost good men in 2001 and he felt what Bergdahl, Wienstein and the others must be feeling. Amerine led a task force that got to work drilling down on every hostage, their location and the efforts to free them. He was stunned to discover that some U.S. hostages being held in Pakistan had no one looking for them. His first order of business was to try to get coordination from the various U.S. agencies. He failed. Fighting over their “rice bowl” is how it is described. Negotiations stalled, agencies squabbled, Bergdahl and others sat in Pakistan waiting for someone to rescue or ransom them.

When Amerine heard that the Taliban “wanted to get rid of Bergdahl” in the spring of 2014 Amerine made his move. Amerine pushed his deal hard, he wanted not just Bergdahl but all seven hostages held in the region. He played his ace card again: Haji Bashir Noorzai. Surprisingly the Taliban agreed. Amerine did not know that Mullah Omar had been dead for a year and that the movement was in disarray. It was a perfect deal.

It was even better because, Noorzai was not a terrorist, he was considered a drug kingpin and unlike the political prisoners he had no political impact on the U.S. or Afghanistan. Ironically in January 2002 Noorzai, like the Taliban Mullahs in Gitmo, had also agreed to work with the U.S. military. His men began to help the U.S. disarm Taliban units in Afghanistan. Eventually he was so productive, he ended up working for the FBI, DEA, CIA and other US agencies. But one of the agencies wanted more, Noorzai was lured to New York in April 2005 and charged with smuggling $50 million in heroin into the U.S. In 2009 he was sentenced to life in prison. So all Amerine needed was a green light to swap Noorzai for all the hostages.

His simple plan was turned down. Furious, disappointed and aware of screw ups that the agencies wanted to keep secret. Amerine then went to Congressman Duncan Hunter. Hunter was outraged at the interagency bickering.

What wasn’t known was that a ransom had been assembled and was to paid under the guise of the DoD paying for information. Something inherent in ever hostage release due to the kidnappers expenses. The problem was the ransom money vanished, stolen by the man who promised to hand it over. The deal evaporated.

One eyewitnesses who met with Secretary of State Chuck before went in front of congress on June 11, 2014 to discuss the Bergdahl release explained all this in private. Republican Duncan Hunter also made the accusation in a letter to Chuck Hagel explaining that his sources knew of a ransom paid by JSOC to release Bergdahl. And more importantly that Chuck Hagel knew of this ransom payment before he testified under oath to Congress. Since the FBI charged Lt Col Jason Amerine with leaking sensitive information its not hard to figure out who was saying what to whom and why. Both President Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry made public statements insisting that the US government does not pay ransoms. The Pentagon simply spun the accusation as money paid for “information” to Bergdahl’s whereabouts.

“No, it was a ransom” says my source who handled the negotiations.

The FBI had also been involved in an attempt to pay of Warren Weinstein’s kidnappers. This also ended badly, because he brought attention to the disastrous way hostage negotiations were being handled, Amerine believes he was then charged by the FBI with leaking classified material to shut him up. Bergdahl and the other hostages remained in Pakistan.

KILLING SPREE

Somewhere around the summer of 2013 the CIA began ramping up its assassinations of Haqqani leaders. Someone (some suspected Haji Mali Khan) was providing the Agency with the intelligence it needed to target members of the terrorist group. The CIA, however, had to ensure that Bergdahl didn’t end up as collateral damage during drone attacks on the Haqqanis.

On September 6, 2013, an airstrike killed Bergdahl’s kidnapper and former keeper Mullah Sangeen Zadran, along with three foreign fighters, in Dargo Mandi, a few miles outside of the Pakistani city of Miranshah. A month later another Bergdahl keeper went down when an early morning drone strike killed the Pakistani Taliban commander Haikimullah Mehsud, leader of Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (Movement of Pakistani Taliban), in the Danday Darpakhel area of North Waziristan. Being Bergdahl’s warden was becoming a liability. America was starting to learn (all over again) that the Haqqani’s were a far more dangerous and efficient group than the Taliban.

It began to look like Wyatt Earp’s crew had time-traveled from the past and been let loose in Pakistan. On November 11, 2013, Nasir Haqqani, the brother of Sirajuddin and son of Jallaludin’s Arab wife, was gunned down in the streets of the capital city, Islamabad. Nasir was the financier of the Haqqani Network, serving as the point person for donors in the Persian Gulf. His death, to put it lightly, was a major blow. And then, in the early morning hours of November 21, 2013, four missiles slammed into a madrassa in the Hangu district of Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, killing several senior Haqqani and Taliban commanders. At this rate, the CIA would soon run out of targets.

According to the Pakistani government, the above were not hunted down and killed by Wyatt Earp and his men. The Pakistanis said the culprit was “Blackwater”, a term used to describe basically any security contractor working at the behest of the CIA . But Blackwater was working in Pakistan, both protecting CIA officers, loading drones and gathering intelligence on high value targets. On December 22, Pakistan ordered the arrest of every U.S. contractor working for the U.S. This extreme reaction to Nasir Haqqani’s killing temporarily shut down the drone program and consequently exposed Blackwater’s role in arming CIA drones and exterminating targets.

A week earlier, the sixth proof-of-life video of Bergdahl appeared, showing the American POW suffering from a seemingly poor mental and physical state of health. But few seemed to care. Bergdahl had slid down the list of American priorities. Ironically, during next month’s State of the Union speech, President Obama made it clear in case the Taliban wasn’t listening to his 2013 State of the Union Speech: “When I took office, nearly 180,000 Americans were serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. Today, all our troops are out of Iraq. More than 60,000 of our troops have already come home from Afghanistan. With Afghan forces now in the lead for their own security, our troops have moved to a support role. Together with our allies, we will complete our mission there by the end of this year, and America’s longest war will finally be over.”

Obama called for a unified Afghanistan and the pursuit of al Qaeda remnants. And in case the Taliban didn’t get his slow pitch regarding Bergdahl and the swap for the Gitmo Five, the president repeated himself once again: “And with the Afghan war ending, this needs to be the year Congress lifts the remaining restrictions on detainee transfers and we close the prison at Guantanamo Bay—because we counter terrorism not just through intelligence and military action, but by remaining true to our Constitutional ideals, and setting an example for the rest of the world.”

INVASION

In a surprising development that applied even more outside pressure to complete a Bergdahl deal, the Pakistan military announced in February 2014 that it would conduct a ground invasion of North Waziristan. The Pakistanis typically make their intentions on these campaigns widely known well in advance to give Pakistani intelligence-supported groups and foreigners plenty of time to move out. Bergdahl’s captors would most likely take their prisoner with them and disappear to some other desert hellhole. Or kill him in a gruesome fashion on video.

It was clear to all stakeholders that if any deal was to be made for Bergdahl and the five Talibs, it had better be simple and quick. Between drone strikes, targeted assassinations, and desperate retribution for those acts, the Haqqanis and Bergdahl might not be around much longer. Jallaludin Haqqani was reeling from his losses. All of his operational sons except Sirajuddin had been killed, and many other family members were dead or worse—disappeared like Haji Mali Khan.

The US, on the other hand, had just added three more members of the network to the Joint Priority Effects List—also known as America’s hit list: Saidullah Jan, a senior commander and financier; Yahya Haqqani, a senior leader involved with military, financial, and propaganda activities; and Muhammad Omar Zadran, a military commander. And now the ISI and the Pakistan military—the network’s onetime sponsors—would conduct a door-to-door search in the heart of the Haqqani domain in North Waziristan.

The US government had been introduced into peace talks using proxies like the Germans, Pakistanis and the Qataris. All had failed. Then when that didn’t work they had used their military might and contracted assassins, which had also failed. In December of 2013, despite all outside appearances of resigned indifference, the secret video demanded as proof-of-life triggered urgent action—at least among the politicians who still gave a damn about Bowe Bergdahl.

According to Republican Representative Duncan Hunter, who pushed for better coordination between military and diplomatic efforts after Jason Amerine bluntly pointed out that the attempts to return hostages ranged from incompetent to non existent. There was a second Special Mission Unit in a failed rescue attempt of Bergdahl in January or February of 2014, as well as a failed ransom payment for Bergdahl. The multi million-dollar payment was made but the Afghan entrusted with delivering the payment vanished. The US had run out of options. As the insider who was at the peace talks with the Qataris acting as middlemen for the Taliban, bluntly puts it, at that point “they were going to kill him [Bergdahl].”

The deal that freed Bergdahl may have been yet another ransom, this one more successful

What Amerine didn’t know was that there was another deal. The first deal, the long deal to break the deadlock on shutting down Gitmo, the deal that started as peace negotiations between the Taliban and the government of Afghanistan. The deal that would release five old school talibs and give them a safe haven in Qatar. Away from Karachi and the control of Pakistan. A deal that would give the Haqqanis the cash they wanted and the Taliban a way out.

President Barack Obama gave a speech at West Point in May of 2014. “When I first spoke at West Point in 2009, we still had more than 100,000 troops in Iraq. We were preparing to surge in Afghanistan. Our counterterrorism efforts were focused on al Qaeda’s core leadership — those who had carried out the 9/11 attacks…Four and a half years later, as you graduate, the landscape has changed. We have removed our troops from Iraq. We are winding down our war in Afghanistan. Al Qaeda’s leadership on the border region between Pakistan and Afghanistan has been decimated, and Osama bin Laden is no more.”

Among the young men and women graduated was a foreigner named Victor Hamad. Hamad was the first Qatari citizen to be awarded a bachelor of military studies from West Point. His father and mother were in attendance flew in on their private jet. The Father also happened to be the Emir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani the ruler of Qatar. After the speech and the celebrations, there was one more bit of business that needed to be done. The ransom for Bergdahl’s release was transferred about the Sheik’s plane under diplomatic protection and whisked back to Qatar. The source for this is rumor is Dewey Clarridge, the man who was intially hired to handle the one million dollar ransom for David Rohde and began the long damnation of Bergdahl as a Taliban sympathizer in his Eclipse intel emails to the military.

HOMEWARD

On June 2, 2014, at 10:30 AM, a Black Hawk touched down at Batai Pass, near Khost. The helicopter was there to recover one man, Bowe Bergdahl, who five years earlier had disappeared from his post at Mest-Makal, about 60 miles southeast. Onboard were American military, paramilitary and civilian members, perhaps the FBI, all dressed in civilian clothes.

Before driving their captive to the pickup point, the lashkar, or small fighting group of Haqqani militia, had shaved Bergdahl’s head, dressed him in clean Pakistani shalwar kameez clothes, and blindfolded him. The lashkar seemed to be enjoying themselves, capturing the event on video and laughingly telling Bergdahl not to come back to Afghanistan: “Go home. Give us back our fighters.” They were giddy. They had clearly won or perhaps they had just confirmed that a ransom had successfully been paid.

Bergdahl’s nickname had been SF, for Special Forces, a reference to his high-energy approach to military life. At the drop off point, before he boarded the Black Hawk, he had asked one of his American rescuers: “SF?” The man nodded.

Bergdahl was broken man. Once aboard the Black Hawk, Bergdahl began sobbing.

When the US Ambassador in Qatar received confirmation that Bergdahl was en route to Bagram Airfield, he alerted US political and military officials. The US, holding up its end of the bargain, flew the Taliban Five from Cuba to Qatar, where they were given a medical examination and new digs for their year of soft lockdown.

As for Qatar’s role in the deal, they insist that for 12 months following the swap that the released Talibs will be prevented from engaging in any activities, contacts, or statements that might be construed as political or terrorist in nature. There is also a travel ban, except for Haj to Mecca. This summer, at the end of one year, the Taliban Five will be free to go home and do as they please.

But what about the equally straightforward American demands for the prisoner swap? Namely that the Taliban must renounce violence and their affiliation with al Qaeda and acknowledge the Afghan constitution, with its inherent rights for women? The Taliban has never publicly stated that it has any intension of meeting these deal points.

By any and all measures, it appeared that the Taliban came out on top of this nebulous deal. They even stole the PR spotlight following Bergdahl’s release. Obama held a press conference in the Rose Garden at the White house, flanked by the Bergdahl’s overwhelmed but cautiously joyous mother and father. The Taliban’s low-res video of them handing over Bergdahl to the hostage recovery team streamed around the globe. The Taliban also drummed up a press release under the name of Mullah Omar: “This huge and vivid triumph requires from all Mujahidin to offer thanks to the Benevolent Creator who accepted the sincere sacrifices of our Mujahid nation and managed the release of these five renowned Mujahidin from the enemy’s clutch.”

And yet, like everything else related to Bergdahl, the outcome was messy. Pakistan, angered that its Taliban client had the temerity to cut them out of the deal and negotiate directly with the Americans via Qatar, began punishing not just the Haqqanis with an invasion of North Waziristan, but also its long-time guests, the Quetta Shura under Mullah Omar.

Two weeks before the hurried prisoner swap there was an important and mostly overlooked event. Since 2009, Tayyeb Afgha, the wispy-bearded Talib negotiator, had refused to leave Qatar and return to Pakistan, presumably out of fear for his personal safety. On May 1, local Pakistani newspapers reported the kidnapping of his two brothers. Security forces in Karachi picked up Younas Afgha, the former Taliban deputy governor of Khost province and the one-time head of the Afghan Red Crescent, the Islamic equivalent of the Red Cross. Tahir Afgha was arrested at his home in Quetta. The ISI was evidently not pleased with the Quetta Shura or its representative.

On June 15, almost two weeks after Bergdahl’s release, Pakistan launched its first major military campaign into North Waziristan, the heart of the Haqqani stronghold. After going house to house in Miranshah and other Haqqani-controlled cities, the Pakistanis proudly displayed photos of captured weapons, chains used to secure prisoners, and other evidence of malfeasance. The images were plastered all over the news. Deep into November, the Pakistanis are still pursuing their offensive, which has displaced 1.5 million people and counting, including 250,000 who have fled across the border into Afghanistan—reversing the usual flow of refugees in the region. The Pakistani military says that it has killed hundreds of insurgents during the campaign, but it is impossible to confirm those claims.

The senior Taliban leadership’s willingness to talk, indirectly or otherwise, with the infidel invaders also angered radical elements of the insurgency. There has been a great shift in the overall Taliban movement. Mullah Omar was a stranger to Osama bin Laden when the radical Saudi first landed in Jalallabad after the Sudanese kicked him out of Khartoum. It was the uneasy marriage between violent wahabist foreign elements of Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda that had plunged the Pashtun nationalist movement of the Taliban into chaos and exile.

After a decade of unrelenting violence, one might think it would seem logical for Mullah Omar to steer the Taliban back to its roots as an Afghan nationalist movement. But, intentionally or not, his death in the spring of 2013 forced the hardliners to kick the hornets nest even harder. Despite being dead for a year, Omar magically made a ghostwritten public statement after Bergdahl’s release, saying the release of the GTMO Five was a “great achievement.” This initially seemed like gloating, but the entire statement also includes verbiage that claims the Taliban intended to focus on national issues, not international terrorism. “I call on all mujahideen in the frontier areas to protect their borders and maintain good relations with neighboring countries on the basis of mutual respect.” Omar’s ghost goes on to say, “Many entities that used to oppose us now have come around to accept the Islamic Emirate as a reality.”

That kind of conciliatory talk infuriated hardline Talibs. Some of them had been fighting since the mid-90’s, driven only by religious fervor and a desire to regain control of their country. This is not a path they were willing to follow, too much blood had been spilled, and it did not align with their core values as freedom fighting jihadists. A young Taliban fighter told reporter Sami Yousafzai, “When I realized the Taliban was really talking face to face with the Americans—the worst enemies of Islam!—my dream of the holy jihad was washed away.”

With heat blasting them from all sides, it’s safe to assume that the gaggle of 40-something, soft-handed religious students are running out of space and time. Commander’s in the field had not seen or heard from the normally reclusive Omar in over a year. They are unable to return to Afghanistan and live there openly, and are now faced with constant harassment in their former safe haven of Pakistan. And the idea that their spiritual leader Mullah Omar was now in peace talks with the Americans was too much to bear.

With all these troubles suddenly facing the Taliban, Qatar looked like an ideal bolt hole for Omar’s aging followers.

THE SPIN

Back in Bowe Bergdahl’s homeland, what was supposed to be a humanitarian coup by freeing America’s hostage turned out to be a political disaster. Right-wing commentators and politicians who had previously hounded Obama for not doing enough to secure the release of Bergdahl now pilloried the president for trading five talibs for one soldier, and a soldier with suspect motives. The lethal reputation of the aging GTMO talibs grew with each Fox News broadcast. Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina described them on-air as the “Taliban Dream Team,” calling for a hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee, claiming the prisoners “have American blood on their hands and surely as night follows day they will return to the fight.” Senator John McCain characterized the five former prisoners as “the hardest of the hard-core” and “the highest high-risk people,” who are “possibly responsible for the deaths of thousands.”

The politicians and talking heads apparently do not realize—or more likely wish to publicly acknowledge—that President George W. Bush released 532 prisoners from GTMO, as compared to the 88 that Obama has discharged. More importantly, in all their fulminating about releasing the Taliban Five in exchange for Bergdahl, the politicians and the pundits never mention the 1,700 to 3,000 Talibs flushed from Parwan detention center at Bagram. Since Bergdahl’s release, Afghan officials have released another 650 prisoners, including ten Pakistanis and other nationalities, from more secret sites on the airfield and quietly sent them home.

The parents of soldiers killed in action following Bergdahl’s disappearance from his base five years prior began appearing on news programs, decrying the human cost of freeing a turncoat. Former platoon members piled on, sullying Bergdahl’s reputation and intent. A Republican lobbyist flack at Capitol Media Partners began providing pro bono PR support to members of Bergdahl’s unit. As they made the rounds of talk shows and worked on a book deal, they repeated the unsubstantiated but politically volatile talking point that “people died looking for Bergdahl.” What they forgot about was a lot of other people had died too, for many other reasons related to and expected of America’s longest war, on both sides.

Fox News contributor Richard Grenell parroted those claims on a Fox program that aired on October 10. Full disclosure: I was also an on-camera guest at the San Diego studio called CoverEdge. When I challenged Grenell to back up his contentions, he couldn’t provide the names of soldiers allegedly killed or produce any other evidence for his statements. He later denied ever meeting me even though Fox broadcast both our separate interviews from the same San Diego studio that day.

Of course, there was still more chicanery to follow. On August 21, the General Accounting Office determined that, in freeing Bergdahl, the president had broken the law not once, but twice: He had failed to notify Congress 30 days before the release or transfer of the GTMO Five, and by spending almost a million dollars to transport the five prisoners from Cuba to Qatar and Bergdahl back to the US, Obama had violated the Antideficiency Act, a 120-year-old law designed to curb unauthorized spending. No one has ever been charged or convicted for breaking this law, and it is doubtful Obama will receive any rebuke stronger than the censure vote on September 9, 2014, which admonished him for willfully breaking the law.

When the Senate Armed Services Committee grilled Defense Secretary Hagel for five hours on the controversial swap, the defense secretary said that 17 inmates had been moved out of GTMO in the past 13 months, and “all of these decisions are part of the brutal, imperfect realities we all deal with in war.” Hagel made no mention of a ransom. He insisted the U.S. did not negotiate with the Haqqanis. “We engaged the Qataris, and they engaged the Taliban. If the Haqqanis were subcontracting with the Taliban, you know the Pakistan Taliban and the Afghan Taliban, there’s a difference there. So we get back into definitions of who has responsibility for whom. I just want to make sure that’s clear in the record, and we can go into a lot more detail.”

Pentagon press secretary Rear Adm. John Kirby announced “There was no money exchanged for Bergdahl’s release”

THE TRUTH EMERGES

As summer gave way to the autumn, the political sniping over Bergdahl died down as the media and politicians turned to domestic issues in the run-up to midterm elections. In early October, Brig. Gen. Kenneth Dahl submitted his report on Bergdahl’s disappearance from his post in Afghanistan and subsequent capture by the Taliban. An Army spokesman announced that commanders would conduct an extensive review of this “initial report” to ensure its accuracy. There was no mention of a deadline, except that the review process would be “lengthy”—as in, long enough to extend past the midterm elections.