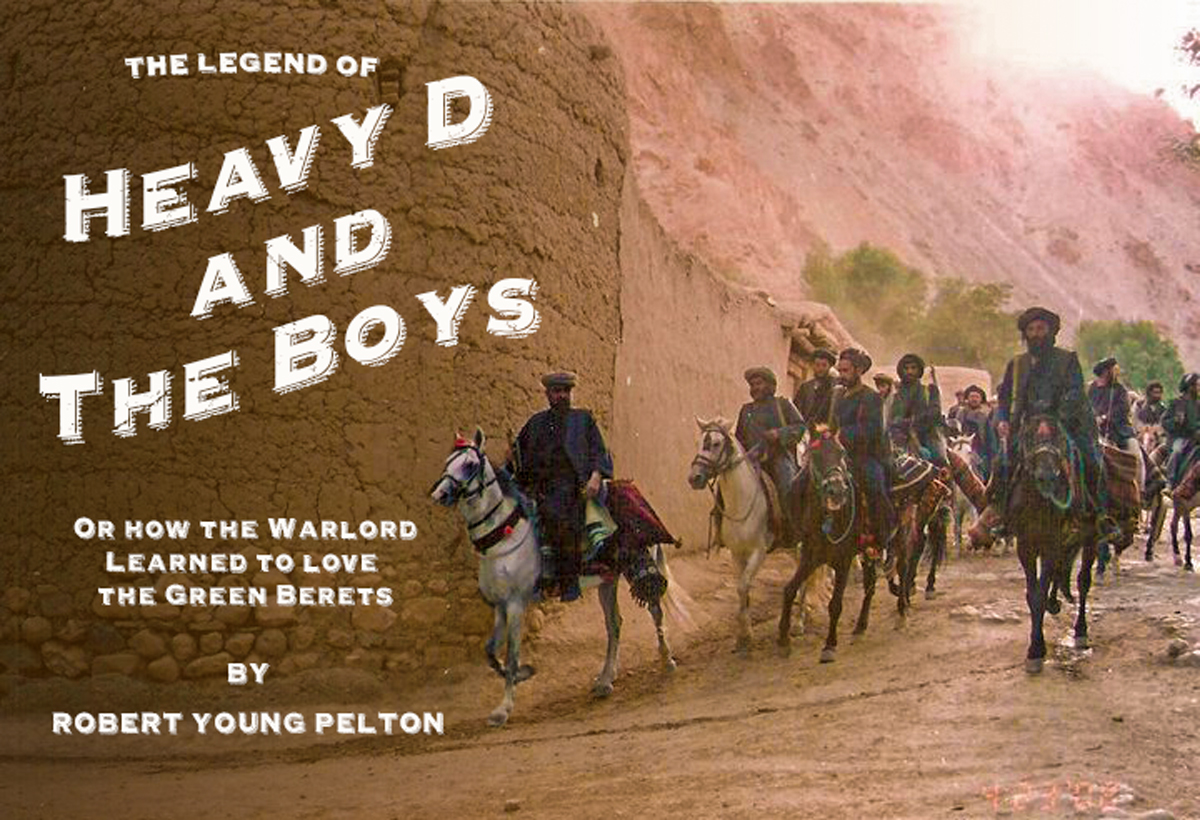

This article on ODA 595, General Dostum, John Walker Lindh and the battle at Qali-i-Jangi was originally published in the March 2002 edition of National Geographic Adventure

THE LEGEND OF HEAVY AND THE BOYS By Robert Young Pelton

The Regulators flew in from Uzbekistan at night on a blacked-out Chinook helicopter. They landed near a mud-walled compound in the remote Darra-e Suf valley in northern Afghanistan. As they began unloading their gear, they were met by Afghans in turbans, their faces wrapped. “It was like that scene in Close Encounters where the aliens meet humans for the first time,” one soldier says later. “Or maybe that scene in Star Wars: These sand people started jabbering in a language we had never heard.” The Americans shouldered their hundred-pound rucksacks while the Afghans hefted the rest of the equipment. The gear seemed to float from the landing site under a procession of brown blankets and turbans.

The next morning, about 60 Afghan cavalry came thundering into the compound. Ten minutes later, another 40 riders galloped up. General Abdul Rashid Dostum had arrived.

“Our mission was simple,” another soldier says. “Support Dostum. They told us, ‘If Dostum wants to go to Kabul, you are going with him. If he wants to take over the whole country, do it. If he goes off the deep end and starts whacking people, advise higher up and maybe pull out.’ This was the most incredibly open mission we have ever done.”

Before heading in-country, the soldiers had been briefed only vaguely about Dostum. They’d heard rumors that he was 80 years old, that he didn’t have use of his right arm. And they’d been told that he was the most powerful anti-Taliban leader in northern Afghanistan. “I thought the guy was this ruthless warlord,” one soldier says. “I assumed he was fricking mean, hard. You know: You better not show any weakness. Then he rides up on horseback with one pant leg untucked, looking like Bluto.”

Dostum dismounted and shook everyone’s hand, then sat on a mound covered with carpets. He talked for half an hour. Dostum’s strategy was now their strategy: to ride roughshod over Taliban positions up the Darra-e Suf Valley, roll north over the Tingi Pass in the Alborz Range, then sweep north across the plains and liberate Mazar-e Sharif, Afghanistan’s second largest city. When the council broke up, Dostum stood and motioned toward the horses. America’s finest were about to fight their first war on horseback in more than a hundred years.

The rocket howls over the roof of General Dostum’s house in Khoda Barq at about 10 p.m. It’s November 26, my second day in Afghanistan, and already I’m in the middle of a hellacious firefight. Although nighttime gunfire is normal in Afghanistan, there is an urgency to the sound of the deep explosions that come from the 19th-century fortress of Qala Jangi, just over a mile east from Khoda Barq, a Soviet-era apartment complex west of Mazar. The heavy shooting, the worried soldiers, the rapid radio chatter—all signal that something ugly is going on over there.

Airstrikes, AC130’s and Hazara guards had killed all but 86 al Qaeda and Taliban fighters

© Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

Meanwhile, I’m hunkered down, waiting for Dostum. I’ve arranged through intermediaries to spend a month with the general, but for the past week, he has been a hundred miles east, trying to subdue Taliban forces that control the city of Kunduz. General Abdul Rashid Dostum is a man who has rarely been interviewed but has often been typecast as a brutal warlord—usually because of his reputation for winning. He is a kingmaker who works the ethnic minority to choose who will rule and who will fail. A man who is said by some journalists to define violence and treachery. (In his book “Taliban”, author Ahmed Rashid reports a tale he heard that Dostum once ordered his men to drag a thief behind a tank until all that was left was a bloody pulp of gore. Rashid later admitted that not only did he not witness it but it the event was fictional. Beyond that, all I know is that Dostum, born a poor peasant, grew up to be a brilliant commander, a general, and a warlord—one of the many regional leaders across Afghanistan whose power derives both from ethnic loyalties and from military strength. That he is known to be a deft alliance maker—and breaker. And that he became the first Afghan commander to take over a major city when he entered Mazar-e Sharif on November 10. It’s an irresistible story, made all the more so by a convincing rumor I’ve been hearing since my arrival: that Dostum triumphed with a little help from his friends—specifically, the Green Berets.

As I wait for Dostum to return, though, the constant chatter of machine guns and the badoom badoom of cannons from an American gunship bombarding the fort—Dostum’s military headquarters—suggest that I might be a bit premature in offering any congratulations on winning the war. I soon learn that yesterday some 400 foreign Taliban prisoners overpowered their guards, broke into arsenals, and took over part of the fortress. Right next to where I am staying. I had first tried to meet the General in May of 1997. At the same moment he was trying to flee Mazar from the Taliban assault. I had jumped a train in Tajikistan, snuck into Uzbekistan and remained holed up in a dusty border town. My attempts to convince the Afghans took place in a building in which men with dark beards sat in from of Tony Montana style palm tree sunset wall paper murals. Finally after two weeks they admitted they could not smuggle me across. This time I had less worries with just a few hours waiting for Uzbek guards to look the other way while we hustled our kit over the blockade Friendship Bridge at night.

At 3:30 a.m., I go to bed. Three hours later, I am awakened by a massive explosion a few yards from the house—another near miss by a rocket fired from inside the fort. The sound of canon fire continues without a break but at a slower pace. In the morning Villagers come out in the crisp, golden light of morning, shivering and tired. Some huddle together to watch the gray pillars of smoke from the bombing runs. Others begin the work of the day without even paying attention to the nearby fighting.

In the afternoon, when I visit the 1985 fort called “Qala i Jangi” or Fort of the Soldiers, bullets sing over my head. Up on the parapets, Dostum’s troops stream toward a gap in the ramparts created yesterday by an errant American 2000 lb bomb. Soldiers run up to the bite in the wall, shoot into the fort, and then scurry back down. I watch a fighter go up to the top, then crumple into a black pile of rags. Astoundingly, after two days of bombardment, the prisoners still control the fort.

ODA 595 Prepares to retrieve the body of Mike Spann from Qala-i-Jangi ©Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

Late in the afternoon, a convoy of mud-spattered off-road vehicles pulls up, and a dozen dusty Americans in tan chocolate chip camo climb out. They have Beretta pistols strapped to their thighs like gunslingers and short M-4 rifles slung across their chests. They’re polite but wary about having their pictures taken as they set up their night-vision scopes. After a final check of their gear, they head into the fortress. Later, I find out that they’ve come hoping to retrieve the body of Central Intelligence Agency officer Johnny Micheal Spann, who was killed by Taliban prisoners—the first American combat casualty in Afghanistan.

Dostum arrives that night, ducking to avoid banging his head as he strides through the guest-house door. He takes my hand in a meaty grip and apologizes for being dirty and tired; he has just driven eight hours on a shattered road from Kunduz. He has two weeks of beard, beetling eyebrows, and a graying brush cut. When Dostum frowns, his features gather into a dark, Stalin-like scowl—his usual expression for formal portraits. But when he smiles, he looks like a naughty 12-year-old.

He sits and makes small talk, then excuses himself to take a shower. When he returns, the dark weariness has lifted. Over chai (tea), he announces good news. He has ended the bloody battle for Kunduz by negotiating with Mullah Faizal and Mullah Nuri, the two most senior Taliban leaders in the north. It seems that the “brutal warlord” has engineered the biggest peaceful surrender in recent Afghan history—more than 5,000 Afghan Taliban fighters and foreign volunteers laid down their arms. He waves the accomplishment aside with a shy smile even as he promises to introduce me to his new trophies—the mullahs. It turns out they’re staying next door, guests in Dostum’s house.

Mullah Faizel, commander of the Taliban Army in the North. © Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

Dostum proves to be significantly more expansive in conversation than his scant press clippings would suggest, and he’s happy to fill me in on his background. Over the next few weeks I privately coin for him a nickname based on the media’s fear and his in person good humor: I call him Heavy D, after the 1980s rapper. “Dostum” is actually a nickname that means “my friend” was born Abdul Rashid in 1954 in the desolate village of Khvajeh Do Kuh, about 90 miles west of Mazar. Headstrong and known to get into fights, was adept at the game of buzkashi, in which horsemen attempt to toss the headless carcass of a calf into a circle. Dating at least to the days of Genghis Khan, the violent game is not so much about scoring as it is about using every dirty trick possible—beating, whipping, kicking—to prevent the opposing team from scoring. Buzkashi is the way Afghan boys learn to ride—and it’s the way Afghan politics is played: There are few rules and the toughest, meanest, and most brutal player takes the prize.

After the seventh grade, Dostum left school to help his father on the family farm. At 16, he started working as a laborer in the government-owned gas refinery in nearby Sheberghan, where he dabbled in union politics.

The people of Dostum’s village were so impressed with his leadership that they recruited 600 men for him to command. It was about this time that Abdul Rashid became “Dostum.” In Uzbek, dost means “friend”; dostum means “my friend.” It was a nickname that the young soldier was given for his habitual way of addressing people. When a local singer wrote a song about “Dostum,” the name stuck. He was quick to defend the weak and if negotiations failed he had no shortage of armed men that would stand beside him.

When a Marxist government came to power in a bloody coup in 1978, the new regime’s radical reforms ignited a guerrilla war with the mujahidin who based themselves in the country’s remote mountain ranges.

Dostum enlisted in the Afghan military—one of the few ways for poor men to escape lives of labor and hardship in rural Afghanistan. He rose through the ranks quickly becoming a paratrooper in 1973, an armored unit in 1978 and Battalion 734 KhAD by 1983. Dostum’s real success was in negotiating enemy commanders to lay down their arms and to join him. He was authorized to transform his Jowyzjani militia into the 53rd Infantry Division in 1988 and ultimately under the Soviet backed regime of Najibullah, he became commander of the 7th Army Corps in charge of all of Northern Afghanistan. Again he began integrating mujahideen into the political military ranks among them his number two against the Taliban Lal Kamadan. At the end of the Soviet period Dostum had 45,000 troops with about half of them as village reserves. If one was to look for the roots of Dostum’s “warlord” reputation it began when he was the direct and most successful enemy of the CIA-backed insurgency of fundamentalist warlords based out of Pakistan. The idea that that Dostum would actually save the day for an embattled America is an irony that has not fully played out.

In the bewildering matrix of Afghan politics, Dostum has frequently—and nimbly—switched allegiances. In the 1980s, as a young army officer in the Soviet-backed government, he fought against the mujahidin. When the regime fell in 1992, three years after the Soviets departed, Dostum fought alongside the mujahidin and helped the Northern Alliance’s legendary Ahmad Shah Massoud battle the fundamentalist Pashtun forces of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and gain control of the capital. The shelling, raping, pillaging, looting, and house-to-house fighting that then befell Kabul stained the name of every mujahidin commander, including Dostum’s, and fueled his reputation for brutality. Today the government of President Ghani has welcomed the fighters of Hekmatyar from exile in Pakistan and is looking to bring the Taliban into the government. All the while ostracizing the now First Vice President Dostum who is currently in exile in Ankara plotting his next move.

But back in 2001, “Warlord” Dostum who was head of the Jumbesh political party had simpler but identical goals: Align with the U.S. to return from exile in Turkey and bring the Taliban into the new government. show Dostum the chapter in Rashid’s book that includes the account of the gruesome execution of the thief. Dostum chuckles and denies the allegation. He freely admits that in two decades of war, abuses have been committed by the troops of every commander. “What else do you expect my enemies to say?” he asks. “That I am kind and gentle? I will let what you see be the truth.”

In 1996, when the Taliban rolled into Kabul, Dostum was forced to retreat to his stronghold in Mazar as the mullahs instituted their version of a pure Islamic state. “At first I thought, Why not let them rule?” he says. “Power is not given to anyone forever. If the Taliban can rule successfully, let them.” A year later, betrayed by his second in command, who had defected to the Taliban, Dostum fled to Turkey. The U.S. refused to work with Dostum until former UN envoy Charlie Santos pointed out to the CIA that the only functioning fighting group besides the Panjshiris of Massoud were Dostum’s Uzbeks. Based on history and dossiers full of Pakistani provided intelligence, the Agency wanted nothing to do with Dostum. Santos pointed out that with Massoud dead, and no Pashtun resistance, Dostum was America’s only hope.

Those among Dostum’s men who had remained in Afghanistan now became guerrilla fighters, moving on horseback holed up in the mountains under the command of his former number two La. Staying off the roads and in the wilds, they could swoop down and attack the Taliban but could not hold the ground. Dostum’s lieutenants would call him in Turkey and tell him how difficult life had become. They had to kill their horses for food. They didn’t have enough cloth for shrouds, so they had to bury dead comrades in burqas. “People demanded that I do something,” says Dostum. “Commanders, clergymen, women—they would all tell me very bitter stories. I was full of emotions. My friends were struggling against the Taliban, and I was sitting there.”

Dostum says that to help him get back into the fray, the former president of Afghanistan, Burhanuddin Rabbani, sliced off about $40,000 from the CIA funds. The CIA had begun to work with Massoud’s people in October of 1999 hoping to pay him to kill Osama bin Laden. The Turks, long staunch enemies of Islamic extremism, contributed a small sum as well, and, on April 22, 2001, General Dostum and 30 men were ferried into northern Afghanistan on Massoud’s aging Soviet helicopters. “That,” says Dostum, “was when the war against terror began.”

Living in caves and raiding Taliban positions, Dostum’s men slowly began to harass the well-entrenched Taliban along the Darra-e Suf. They moved and attacked mostly at night, riding small, wiry Afghan horses that are well suited to steep slopes and long desert walks. “The money was hardly enough for feeding my horses,” Dostum says. “They had tanks, air force, and artillery. We fought with nothing but hope.”

Then came September 11. Despite actively fighting the Taliban, it was not until Santos introduced Dostum to JSOC that the United States might want to give him some help. Even the CIA was reticent to land paramilitaries and officers to set up the conditions for an Special Forces ODA to be inserted. At the last minute the Agency was told by the SF ground commander that his men were going in with or without the Agency. A small group of CIA that included Mike Spann, flew in to the Darra-e Suf the day before ODA 595 would land.

Now three weeks later the war was supposed to be over. The Taliban had surrendered at Qali i Jangi to CIA officer JR and Dostum and surrenders were under way in Kunduz. The B-Team had already set up shop at the Turkish School in Mazar and was getting ready for the push to Tora Bora. Until a group of 480 al Qaeda and talibs showed up at the gates of Mazar. Dostum and the Green Berets drove by them as they headed for Kunduz.

The morning after Heavy D’s return from Kunduz, he greets me with a deep, booming “Howareyou?” Today, he tells me, he is eager for me to meet his trophy mullahs.

Next door, in Dostum’s pink house, Mullah Faizal and Mullah Nuri sit on pillows in a small room. These are two of the Taliban who chased Dostum out of Mazar in May 1997, but still he treats them more like honored guests than prisoners of war. Faizal has his prosthetic leg off. He is a thick man with a pug nose, bad skin, tiny teeth, and a cruel stare. Nuri has the black look of a Pashtun who has endured a lifetime of war. Wrapped in blankets, members of the mullahs’ entourage fix me with soulless stares. Nuri is chatty, although he often looks to the silent Faizal before answering my questions. During the Taliban’s reign, thousands of Hazara Shias were murdered in northern Afghanistan; the mullahs are unrepentant. “We fought for an idea,” says Nuri. “We did all that we could. Now we hope that America will not be cruel to the Afghan people.”

That afternoon, Dostum and I set off for the fort, where the uprising has been all but quelled. He brings the mullahs along, to show them the havoc incited by their foreign volunteers. Perhaps they’ll convince any surviving prisoners to surrender.

After four days of bombardment, the interior of the fort is a scene of utter devastation. Blackened, twisted vehicles are perforated with thousands of jagged holes. The crumpled bodies of prisoners, frozen in agony, are scattered everywhere. Most of the fallen look as if they were killed instantly. Some are in pieces; others have been flattened by tank treads. More than 400 prisoners are said to have died;

I count only about 50 bodies in the courtyard. The estimated 30 Alliance soldiers who died have already been taken away by their friends. When an American team finally recovered Spann’s body, they discovered it had been booby-trapped with a live grenade (which they removed without incident).

It is also rumored that there are many dead and at least two live prisoners holed up in the subterranean bomb shelter. The entrance to the bunker was pierced by cannon shots and is blackened from explosions. Dostum’s men have been throwing down grenades and pouring in gasoline and lighting it, but the foreign Taliban refuse to come up. Dostum implores the mullahs to call down to the bunker and tell the remaining men to surrender. Mullah Faizal and Mullah Nuri refuse: They claim they don’t know these people.

There are 86 al Qaeda fighter in the basement, including John Walker Lindh. Mullah Nuri insists he doesn’t know them and they refuse to come up.

© Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

The trapped Taliban volunteers, it seems, remain hungry for martyrdom. A day later—Thursday, five days since the uprising broke out—they are still firing sporadically at soldiers removing bodies from the courtyard of the fortress. At least two Red Cross workers who descend into the bunker are shot and wounded.

Later that week, Dostum casually mentions that 3,000 other foreign fighters from the surrender at Kunduz are in a Soviet-era prison in the city of Sheberghan, 80 miles west. Anticipating more fireworks, I head there with him and move into another of his residences, a huge, high-walled compound that includes a mosque and, improbably, an unfinished health-club complex.

By the time the team had arrived in Qali-i-Jangi they were gaunt, sick but eager to keep up the fight. Over 5000 Taliban remained hidden in surrounding villages. © Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

Some American soldiers are billeted upstairs in the guest houses; men in camo pants run up and down the stairs. Their rooms are filled with green Army cots, dirty brown packs, and green flight bags. Rifles, night-vision gear, and boots are strewn everywhere. I head downstairs and discover a group of soldiers bantering cheerfully, mostly in southern accents. They’ve just finished installing a satellite TV. When the television begins to blare, the men stare at the screen. “We haven’t seen a TV or news in two months,” one soldier says apologetically. Transfixed, they watch the Christmas tree being lit in Rockefeller Center.

These are the soldiers I saw back at Qala Jangi preparing to go in and retrieve the body of the dead CIA agent, Mike Spann. “Don’t I know you?” one of them says. “Aren’t you the guy who goes to all those dangerous places?”

It feels more than a bit odd to be recognized for my books and TV show—as someone who specializes in traveling to the world’s hot spots—while poking around a war in Afghanistan. It feels even more odd when I discover that these are Green Berets—soldiers who truly specialize in the world’s hot spots. But I never travel without a few “Mr. DP” hats, so I dig them out of my bag and pass them around.

Over the ensuing days, I take every opportunity to spend time in these makeshift barracks, particularly once I discover that this is the very unit of Green Berets that I’d been hearing rumors about—this is Dostum’s covert support team. At night we sit around talking over stainless steel cups of coffee. Some details of their mission they can’t discuss. Some are provided by Dostum and others. But the story gradually emerges.

There are twelve Green Berets here and two Air Force forward air controllers. Green Berets work in secrecy, so only their first names can be used: There’s Andy, the slow-talking weapons expert who is never without his grenade launcher; back home, he keeps the guns in his collections loaded “so they are ready when I am.” Both he and Paul, a quiet, bespectacled warrant officer, have been in the unit 11 years. Then there’s Steve, a well-mannered southern medic; Pete, the burly chaw spitter; Mark, their blond, midwestern captain; and so on. It’s like a casting call for The Dirty Dozen. Their motto is “To Free the Oppressed”—something they have done so far in this war with no civilian casualties, no blowback, and no regrets.

In between conflict there was time to celebrate. A typical meal at Dostum’s guesthouse.

© Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

These soldiers, I soon realize, come from much the same background as Dostum’s: sons of miners, farmers, and factory workers; some are men whose only way out of poverty is the military. They range in age from mid-20s to early 40’s. They are men with wives, children, mortgages, bills. Men who are the Army’s elite, who are college educated and fluent in several languages, yet who are paid little more than a manager at McDonald’s. They spend every day training for war, teaching other armies about war, and waiting for the call to fight in the next war.

They are direct military descendants of the Devil’s Brigade, a joint Canadian-American unit that fought in Italy during the Second World War. That group was disbanded and then re-formed in the early 1950s as Special Forces, which John F. Kennedy later nicknamed the Green Berets. The men I’m staying with have dubbed their unit the Regulators, after the 19th-century cowboys who were hired by cattle barons to guard their herds from rustlers. The Regulators have served in the gulf war, Somalia, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and in other places they can’t talk about. Their home base is Fort Campbell, Kentucky, but they spend only a few months of the year there. The rest of the time they travel.

On the morning of September 11, the team was returning to base after an all-night training exercise. “The post was in an uproar,” says Paul. No one knew just when or where the team would be sent. They cleaned and stowed their gear and awaited the order. And waited. There was talk that the team might be split up—rumors of differences with a commanding officer who didn’t appreciate the traditional independence of the Green Berets. They were all quitting demanding to be sent to other units rather than put up with new commander ideas on what soldiering was. But 9/11 changed all that. Toward the end of September, the word came down: “Pack your shit.”

Fifteen days later, the team boarded a C-5 Galaxy with a secret flight plan. The Regulators’ final destination turned out to be Uzbekistan, where they spent a week building a tent city and waiting for a mission. “We were at the right place at the right time,” says Steve. “Fifty tents later, they told us to pack our shit again.”

First arrival on the Observation Post. Now the tiny group of Americans need to show General Dostum what they can do.

“We had two days to plan,” another Regulator says. “The CIA gave us a briefing.” Although the Regulators were among the first, other small teams of U.S. forces would soon be airlifted in for similar missions, a response to Dostum’s request for American assistance to be sent to other Northern Alliance commanders. In an effort to trim Dostum’s control the CIA would insist that rival commander Ustad Atta Mohammed get his own Green Beret escort several weeks later as he raced Dostum to claim Mazar. Surprisingly Dostum agreed. Once they hit the ground, the Regulators would be writing their own game plan. “Our commanders said they didn’t know what to expect, but at least they were honest enough to admit it,” the Green Beret continues. “They said, ‘You guys will be on the ground; you figure it out.’ ”

Within half an hour of meeting Dostum at the mud-walled compound in the Darra-e Suf, the Regulators swung into action. Some stayed behind to handle logistics and supplies. The rest mounted up and rode north. “It was pretty painful,” Paul says. “They use simple wooden saddles covered with a piece of carpet, and short stirrups that put our knees up by our heads. The first words I wanted to learn in Dari were, ‘How do you make him stop?”

Their most important immediate order of business was to establish themselves in Dostum’s eyes. “The first thing we wanted to do was to say to Dostum, ‘The Americans are here,’ ” Paul explains, “and to make it a fearsome prospect to mess with us.” The Americans set up their gear at Dostum’s command post—which overlooked Taliban positions about six miles away—and immediately began the process of calling in close air support, or CAS. “You see the village; you see the bunkers,” says a second Steve, one of the two Air Force men attached to the team to help coordinate air strikes. “You call in an airplane; you say, ‘Can you see that place? There are tanks. You see this grid? Drop a bomb on that grid.’ Pretty straightforward stuff.”

It took a few hours for bombers to arrive from their carriers. At first, the planes wouldn’t fly below 15,000 feet—the brass was worried about surface-to-air missiles—so targeting was sketchy. But coordination soon improved, and the improbable allies fell into a rhythm: The Americans would bomb; Dostum’s men would attack.

A crude videotape made by one of Dostum’s men shows a battle in the rolling hills of the Darra-e Suf, where the yellow grass contrasts with the deep blue sky. The Americans, up on the ridge, are using GPS units to finalize coordinates. Down below, small Afghan horses are nipping the dry grass on the safe side of the hill, their riders chatting while awaiting the order to charge. The horses cast long shadows in the late afternoon. The only sign that something is about to happen is a white contrail high in the sky. The radio crackles with call signs and traffic broadcast between bombardiers and the American soldiers. First, a soft gray cloud of smoke rises in a lazy ring. Then the concussion: ka-RUMPH!

The tape now shows Dostum, leaning against a mud wall, watching through large binoculars. The dirty gray mushroom cloud slowly bends in the wind. Dostum stays in contact with the Americans by radio, working to help focus the bombing: a man with a seventh-grade education directing the fire of the world’s most powerful military.

Ka-RUMPH! More hits: Tall, fat smoke plumes cast moving shadows on the grass. The riders mount their horses, check their weapons, and begin the one-kilometer sprint to the Taliban front lines. There’s the erratic chatter of AK-47s and the deep dut dut dut dut of Taliban machine guns. Then the radios are jammed with Dostum’s men shouting and celebrating. The Taliban are running.

The videotape cuts to the next morning. Dostum’s men are touring the battle scene. The twisted rag doll bodies of dead Taliban fighters lie heads back, fingers clutched, legs sprawled as if they fell running. Dostum’s men kick the corpses into the trenches and cover them with the tan dirt, not bothering to count the dead.

The Regulators were joined by at least three CIA officers kitted in full combat gear, including a 32-year-old ex-Marine named Mike Spann. “We were surprised at how good they were,” says Captain Mark. “What we are doing now has not occurred since Vietnam. Up until now the CIA has been hog-tied. Now the CIA and spec ops have been let loose.”

Each night, Dostum would sit down with the Americans and lay out the battle plan for the next day. “He would say he is going to attack at about 2 p.m.,” says Air Force Steve. “So we would put in for priority for the planes.” The team’s primary weapons were not pistols or rifles; they were the most fearsome tools in the American arsenal: F-18s, F-16s, F-14s, and B-52s. They chose not bullets or grenades but ordnance that ranged from Maverick missiles to laser-guided bombs.

In contrast to the Americans’ high-tech warfare, some of Dostum’s tactics would have seemed familiar to the British troops who tried and failed to pacify this region in the 19th century. Before the arrival of the Americans, Dostum fought mostly at night. “He couldn’t expose his small force to Taliban missile strikes,” explains Captain Mark, “so they would hit and retreat. He never sacrificed his men. He would take a village by getting the mounted guys up close. When it looked like they would break the back of the position, he would ride through as fast as he could and keep the Taliban on the run.”

With their knowledge of military history, the Regulators appreciated the ironies of this strange war: “The Taliban had gone from the ‘muj’ style of fighting—in the mountains, on horseback—to working in mechanized columns,” says Will, another member of 595. That heavy reliance on tanks and trucks meant the Taliban wound up fighting a defensive, Russian-style war. “Then, here is Dostum,” says Will, “a guy trained in tanks who’s using tactics developed in Genghis Khan’s time.”

The Regulators’ job was to invent a new form of warfare: coordinating lightly armed horseback attacks with massive applications of American air power—all without hitting civilians or friendly forces. “In an air attack,” says Air Force Steve, “you do one of two things. You can bomb it until there is no resistance, or you bomb and, as soon as the bomb goes off, you charge. By the time they come up and look, you are on them.” The latter approach was well suited to Dostum’s style of attack. “A cavalry charge is an amazing thing,” Will says. “At a full gallop, it’s a smooth ride. The Afghans shoot from horseback, but there is no aiming in this country. It’s more like, ‘I am coming to get you—whether I hit you is another story.’ It’s Old World combat at its finest.

“There’s one time I’ll never forget,” he says. “The Taliban had dug-in, trench-line bunkers shooting machine guns, heavy ma-chine guns, and RPGs [rocket-propelled grenades]. We had an entire 250-man cavalry ready to charge.” The Regulators wanted Dostum’s right-hand man, Commander Lal, to hold off while they got their aircraft in position, but Lal had already given the order. In seconds, 250 men on horseback were thundering toward the Taliban position a mere 1,500 meters away.

“We only had the time it takes 250 horses to travel 1,500 meters, so I told the pilot to step on it,” Will says. “I looked at Lahl and said, ‘Bombs away.’ We had 30 seconds till impact; meanwhile, the Afghan horde is screaming down this ridgeline. It was right at dark. You could see machine gun fire from both positions. You could see horses falling.” An outcrop obscured views of the last 250 meters to the target. The lead horsemen disappeared behind the rocks, and the Regulators all held their breath, praying the bombs would reach the bunkers before the cavalry did. “Three or four bombs hit right in the middle of the enemy position,” says Will. “Almost immediately after the bombs exploded, the horses swept across the objective—the enemy was so shell-shocked. I could see the horses blasting out the other side. It was the finest sight I ever saw. The men were thrilled; they were so happy. It wasn’t done perfectly, but it will never be forgotten.”

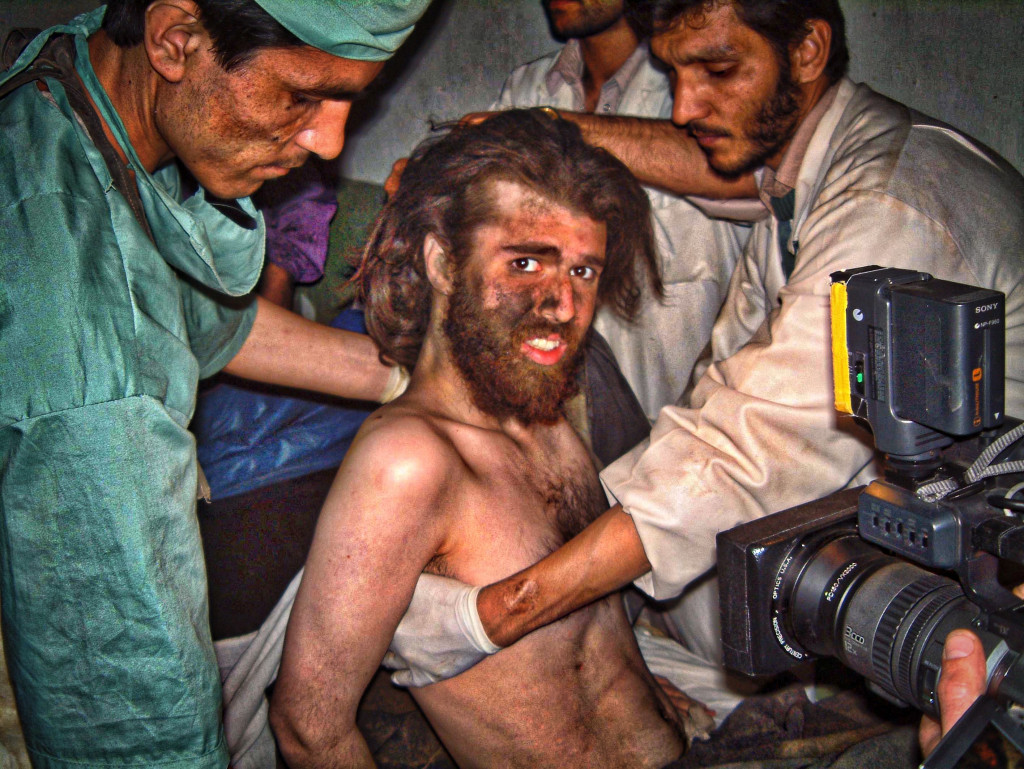

Around eight o’clock on Saturday night, while I’m talking with the Green Berets, one of Dostum’s men comes into the house and asks us to follow him outside. Beyond the high steel gates is a confusion of trucks, headlights, and guns, and the sound of men moaning in pain. Lined up against a wall is the most pathetic display of humanity I have ever seen: the survivors of the bunker at Qala Jangi fortress. Dostum’s men had finally flooded them out by sluicing frigid water into the subterranean room. Instead of the expected handful of holdouts, no fewer than 86 foreign Taliban emerged after a week in the agonizing dark and cold—starved, deaf, hypothermic, wounded, and exhausted. Their captors brought them here en route to the Sheberghan prison.

They send off steam in the cold night, their brown skin white with dust. Some hide their faces, others convulse and shiver. I talk to an Iraqi, as well as to Pakistanis and Saudis—all of whom speak English. On another truck are the seriously wounded. Some cry out in pain, some are weeping, and others lie still, their faces frozen in deathly grimaces.

They put the prisoners back on the truck. A few minutes later, one of Dostum’s men runs up breathlessly, saying there is an American in the hospital. I grab my cameras and ask Bill, a pensive Green Beret medic, to come with me.

The soldiers stay well away from the al Qaeda prisoners as I interview them. They have been blowing themselves up with grenades. © Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

The scene at the hospital is ugly. The warm smell of gangrene and human waste hits me as I open the door to the triage room. Shattered, bearded men lie everywhere on stretchers, covered by thin blue sheets. The doctors huddle around a steel-drum stove, smiling and talking, oblivious to the pain and suffering around them. In the back, a doctor leans over a man with a smoke-blackened face, wild black hair, and an unkempt beard. He lies staring at the ceiling. The doctor yells in halting English, “What your name?” He jabs at the half-conscious man’s face. “Open your eyes! What your name? Where you from?” The man finally answers. “John,” he says. “Washington, D.C.”

The man is terribly thin and severely hypothermic. At first he is hostile, like a kitten baring its claws. He won’t tell me who to contact, or provide any information that would get him out of the crudely equipped hospital. I convince the staff to move him to an upstairs bed, where Bill inserts an IV of Hespan into the man’s dehydrated body to increase blood circulation. As Bill checks for wounds, he talks to the young man briefly in Arabic. I tell the prisoner where he is and who he’s talking to. Bill finds a shrapnel wound in the emaciated man’s right upper thigh and wounds from grenade shrapnel in his back; he also finds that part of the second toe on his left foot has been shot away.

John Walker Lindh was the second Irish American jihadi I had met who was trained in Bin Laden’s camps. He refused to talk to his parents and he was taken back to our guesthouse for his protection. © Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

As the Hespan drips into his veins, I fire up the video camera, and the man begins to tell his story. His name, he says, is John Walker. He studied Arabic in Yemen and then enrolled in a madrasah, or religious school, in northern Pakistan. He says it was an area sympathetic to the Taliban and that his heart went out to them.

Six months ago, he traveled to Kabul with some Pakistanis to join the Taliban. Since he can’t speak Urdu, he was assigned to the Arab-speaking branch of Ansar (“the helpers”), a faction that Walker claims is sponsored by Osama bin Laden—whom Walker says he saw many times in the training camps and on the front lines.

He ended up in the Takhar Province, in the northeastern part of the country. Then the war began. After the American bombing campaign decimated their forces, Walker and members of his unit fled on foot nearly a hundred miles west to Kunduz—all for nothing, as it turned out. Mullah Faizal and Mullah Nuri soon surrendered Kunduz to Dostum, and Walker was imprisoned with the other foreign volunteers in the bunker at Qala Jangi.

When I look at the terrible conditions and the predicament that Walker is in, I have to ask him if this is what he expected.

“Definitely.”

Was his goal to become martyred?

“It is the goal of every Muslim.”

Then the morphine begins to kick in. I suggest to Bill that we remove Walker from the hospital, where he might be killed by other patients, many of whom were fighting against him at the fortress. We transfer him to Dostum’s house, and the next day he’s spirited away at the same time that his story is being broadcast around the world.

When the videotape of my interview with Walker hits the airwaves back in the U.S., the country focuses its white-hot anger on him, and some of that anger spills over onto me. In the conservative press I am criticized for being too gentle in my questioning of an obvious traitor, on the left for cold-bloodedly tricking a helpless boy into incriminating himself.

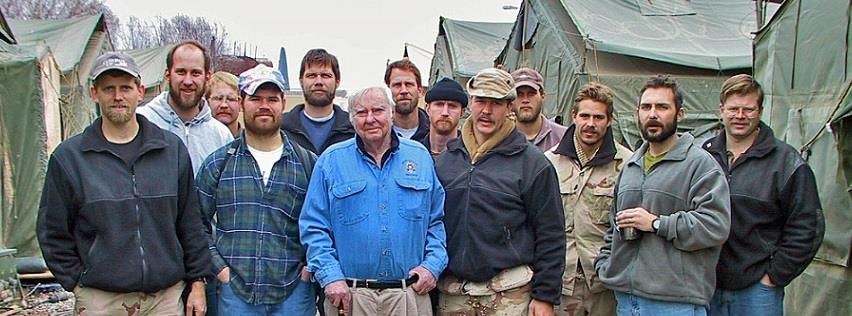

The team was ordered to exile to meet Donald Rumsfeld and be interviewed by Robin Moore. What happened next was the first of many distortions and fictional retelling of their story. This is the back jacket of The Hunt for Bin Laden ghostwritten by the late Jack Idema and published as non fiction by Random House editor Bob Loomis. The book was quietly taken out of print.

If you drive west from Mazar, past Qala Jangi, past Khoda Barq, past the ancient, crumbling city of Balkh, and head south toward a ridge of snow-dusted mountains called the Alborz Range, you will see a gap—the Tingi Pass. This is where the Taliban made their last stand. The Green Berets call it the Gap of Doom.

Two of the Green Berets I’ve been chatting with—Andy and Paul, the pair with the longest tenure in the company—have decided that I need to see this place for myself, or maybe simply that they need to go see it again one last time. We jump in a Toyota off-road vehicle and set off. Soon we’re winding past an ancient brick bridge that crosses a roaring gorge; on the west side are large caves that shepherds have scooped out of the soft rock over the centuries.

As we drive, Paul tells me that, back in the U.S., even the Regulators are subject to a military culture of rules and red tape. Planning a one-day live-ammo training exercise can require six months of paperwork. “If there is no enemy, then bureaucracy is the enemy,” he says. But on the ground in Afghanistan, they’re on their own. The greatest restrictions they face have been placed on them by Dostum himself. “Dostum was very concerned about us getting too close to the battlefield,” Captain Mark had told me back at the barracks. “In the last two semi-wars we have been in, every time American soldiers get killed we pull out. That is one of the premises Osama bin Laden operates under.” Dostum wasn’t about to let an American casualty put a premature end to his battle plan.

Their closest call came toward the end of the campaign, before they’d reached the Tingi Pass; I’d gotten an account of it last night from Mike, a big, bearded, soft-spoken soldier. The conflict began with several hundred Taliban troops moving into positions on an adjacent hill. Outmanned, the Green Berets decided to move out on horseback. They had gone only about 600 meters when they started taking fire. “I figured I could whip my horse and run across an open area,” Mike said. “I whip my horse, it takes three steps, and stops. The rounds are zinging over my head. Somehow I make it across the open area. I get off the horse and say, ‘Screw this; I’m walking.’

“We set up in a bomb crater and used it as our bunker. We were receiving more fire. It was somewhere between harassing and accurate—enough to keep our heads down. We called in a couple of bomb strikes. We could see a bunch of Taliban come out of another bunker complex off to the south and disappear behind a hill. It took about an hour to get the aircraft. All the while, we could see troops moving and disappearing. I’m looking through the optics while rounds are zinging all around us.” At this point in the tale, Mike nodded toward Paul, who was sitting next to him on the couch at Dostum’s guest house. “Paul here is busy shooting at guys. What we didn’t realize was that the Taliban who we saw coming out of the bunker had gone into the low ground and were sprinting up the hills at us in a flanking maneuver.

“Our Afghans are running out of ammo. Their subcommander has told us at least six times over the radio to get out of there. You have to understand: Dostum had told them, ‘If an American gets hurt . . . you die.’ We were focused on calling in an air strike to take out this truck that had rumbled into view, and now RPG rounds are flying over our heads. We’re not about to stand up and watch what’s going on. The pilot asked us, ‘What’s the effect [of the bomb attack on the truck]?’ We yell over the radio, ‘We don’t know! We’re not lifting our heads up!’

“When we turn around and notice what’s going on, we see our Afghans have split.”

The team decided to call in a B-52 strike practically on their own position—a drastic move considering the planes were flying above 15,000 feet. The enemy was 700 meters out and moving quickly. “Matt yelled, ‘Duck your head and get down!’ And that pilot dropped a shitload of bombs,” Mike said. “You felt the air leave. After the bombs hit, I peeked over the side of the bunker; our horses were gone. We grabbed our stuff and ran.”

The team knew that their story would be stolen, rewritten and misused as Rumsfeld and others seized the moment. © Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

Paul, Andy, and I drive past villages of round, domed huts, past a checkpoint manned by Dostum’s men, and up along the winding road to the Tingi Pass. Three years of drought have broken: A cold rain pours down in gray sheets. We pass the twisted, stripped wrecks of trucks and Toyotas. Afghans in a blue truck are scavenging for parts. The two Green Berets are solemn; they insist on driving through the gap so they can tell their story from the right perspective.

We wind through the tight pass alongside a swollen mountain river, go over the pass, then head a kilometer down the south side of the divide and stop at a freshly mudded house. We get out of the jeep and stand in the rain and slick mud. Paul picks up the story, raindrops dotting his gold-rimmed, government-issue glasses.

“We kept moving north on horseback, but at that point, no one could tell where the front line was anymore. Once we hit Keshendeh-ye Bala, we picked up a road and followed it north in a truck Dostum’s men had captured from the Taliban. At eight that night, we pulled in to Shulgareh, which is the biggest town in the valley. We were ready to throw down the mattress and settle in for the night when one of the security guards came up with a radio and said that Dostum needed someone to go up to the front to call in aircraft. We jumped in the back of a truck and drove up to Dostum’s HQ here in this house.”

In the courtyard, a soft-eyed cow tries to eat spilled oats just beyond its reach. A hundred yards away, villagers stand against a long compound. They huddle in brown blankets, trying to avoid the soaking rain. Paul points to a misty, triangular peak that forms one side of the gap. It served as Paul’s command post.

“When we climbed up to the top of that hill, we could see the Taliban on the other side, regrouping for the final attempt to stop us. They were setting up fixed positions—bunkers with Y-shaped fighting trenches—on the northern side of the gap. It works against tanks, but it’s plain stupid in this terrain. We had unrestricted movement into the gap, which gave us the high ground.”

Andy chimes in. “Whoever gets the high ground first wins the wars here.” From their perch on the east side of the gorge, the Green Berets could shoot directly into the trenches of the Taliban.

“Once the plane got there, it circled about six times,” Paul says. “Every time the plane would circle, the Taliban would run behind their bunker. After four times or so, they didn’t get bombed, so they just stayed there.

I targeted a spot right next to this guy’s head. I was sick of this guy running back and forth getting ammo. Then the bombs are dropped, and I look through the scope and see body parts flying everywhere. We moved our targeting up along the ridgeline to the second bunker. Same thing: We identity it and boom! No more Taliban. I target the third bunker. They just can’t figure it out. The bomb lands and hits and bam! After that hit, all of them took off on foot to Mazar. And that ended the resistance.” As the three of us climb back into our vehicle, I glance at the battlefield. All I see is grass growing beside abandoned trenches. Only Paul and Andy are able to appreciate what happened here.

Early in the afternoon on November 10, Dostum reached Mazar. His men rounded up vehicles that the Taliban had left behind, and Heavy D entered the city as a conquering hero, standing through the sunroof of a Toyota Land Cruiser. The crowds quickly grew; people threw money in the air for good luck. Dostum’s first stop was the blue mosque at the tomb of Hazrat Ali, the revered son-in-law of the Prophet. Men wept as the imam prayed and thanked Dostum for deliverance.

A local mullah sings a prayer of deliverance and thanks to Dostum. © Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

The joy was short-lived. It turned out that 900 Pakistani Taliban had been left behind in a madrasah in the center of a compound about the size of a city block, and they were ready to fight to the death. Dostum and his commanders wanted to negotiate, but the foreign Taliban shot and killed their peace envoys, which left Al-liance leaders with little choice. “We had hardened fighters holed up in the middle of an urban area who wanted to die,” says Will. “And we were going to oblige them.”

The team set up on the roof of a building about 400 meters from the madrasah and called in a strike. When the two aircraft were on location, the Green Berets radioed Alliance commanders to evacuate civilians from the area. The pilots, however, could not lock in on the laser-sighting device that the team was using to identify the target. The madrasah was surrounded for about a mile on each side by identical buildings, which made it difficult for the pilots to pick out the school. “Finally, the pilot says he has the target in sight. I asked him to describe it, just to be sure,” says Will. “He described the building we were sitting on to a T.” Finally, Air Force Steve guided the pilot to the correct building, and he dropped the ordnance: direct hit.

The team cleared him for immediate re-attack, but the pilot radioed back that he had “hung a bomb”—a bomb had not released. When the pilot radioed that he needed to return to base, the other pilot swung into action. On the next pass, three more bombs went through the hole in the roof made by the first bomb, killing most of the holdouts inside.

Under intense pressure, the Regulators had called in a perfect surgical strike—a bomb drop in a crowded urban area without a single civilian casualty. “This is the first close-air-support strike in years in an urban area,” says Air Force Steve. “It was old-fashioned professionalism. The whole team jelled.”

The steel gate to the guest house opens, and Dostum strolls out, hands in pockets, and is ushered into a black Audi Quattro with tinted windows. Dozens of dark-eyed men in turbans scramble into battered Toyota pickup trucks and assorted four-wheel-drive vehicles. Armored personnel carriers jerk to life in clouds of black diesel exhaust. It’s three weeks after the madrasah bombing, and word has come down that 3,000 Taliban are still occupying the city and environs of Balkh, Alexander the Great’s old walled capital, a few miles west of Mazar. Dostum has decided to clean up the region’s last remaining pocket of Taliban himself.

I ride in the warlord’s communications truck, a white Land Cruiser. The Regulators rush to catch up in two mud-covered cars. We roll past weathered villages unchanged in two millennia. Abandoned Soviet-era tanks are scattered about the flat countryside like dinosaur skeletons.

This part of Afghanistan is ancient, arid, windblown—and is the real cradle of its history and wealth. This is where Alexander ruled, where Zoroaster was born, where Buddhists came on pilgrimages, a center of art, poetry, and study where lions were hunted and where Genghis Khan came to conquer. Now, in a scene that has been repeated over and over for the past 2,000 years, a warlord is arriving.

In a village on the outskirts of Balkh, the convoy rumbles to a halt near an ancient castle that is now a rounded mound of tan mud. The truck-mounted ZU antiaircraft guns are cranked down to eye level. Twenty Urgan missiles point toward the village. Dostum’s men load RPGs and check their ammo drums. About 200 men have taken up positions around the village, eyeing ragged locals, who stare back from a careful distance. It feels like a scene out of a bad Mexican movie.

After a cinematic pause to allow the implications of his arrival to sink in, Dostum phones the village leadership from the Audi: Send out your weapons and any fighters or we’re going in. The deadline is noon.

The general climbs out of the tiny black car and tucks his hands into his belt. He rolls in a John Wayne walk to Commander Lal, who’s in charge of the standoff. The two Afghan leaders study a map with Captain Mark, just in case air strikes are needed. When noon comes and goes, I expect the order to fire. I am surprised, then, to see Dostum wrap his blue turban around his head and chin and stride into the village . . . to talk.

Ironically, it was this sort of diplomatic triumph—the surrender at Kunduz just before my arrival—and not a battle that gave the Regulators their most bitter experience of the war. “We thought Kunduz was [going to be] a full-scale attack,” says Captain Mark. “When we got there, we were sitting on our asses.” It was while they watched the drawn-out surrender that Mike Spann was attacked at Qala Jangi and the uprising began. “This was a guy we considered part of our unit,” says Mark. “If we had been there, Mike’s death would not have happened.”

When they got word of the incident, the unit desperately wanted to get back to the prison. “The info I had was that he was MIA,” Mark says. “We thought he was wounded. The old creed is that we never leave a guy behind.” The Regulators wanted to find the prisoners who had killed Spann and attacked a second CIA man who was questioning the Taliban. “We begged,” Mark says, “but we were told to stay away.” (In the end, the Regulators wouldn’t get clearance to enter Qala Jangi until the uprising was over.)

Commander Abdul Karim Fakir, who was in charge of the fortress while Dostum was in Kunduz, had worked with the Green Berets since they landed in Afghanistan. “I saw this look in Fakir’s eyes,” says Mark, “like, Why didn’t you help?”

Dostum, triumphant on a return to the simple village of his brith. © Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

Dostum has not been home in five years to the village of Khvajeh Do Kuh. His father is old. Two weeks after Dostum descended on Balkh, things have calmed down, so the warlord climbs into the front passenger seat of a Nissan, and we head across a sandstorm-blasted desert. This time there is no convoy; just a son paying his respects to his father. As we drive through a drought-ravaged wasteland, he points out battlefields and the sites of ambushes and skirmishes. Dostum tells me that he has fought on every inch of Afghan soil and can recite the names of his men who have died, describe each battle in detail, and tell you what he has learned from every encounter. He says it sadly.

A few yards before the turnoff to Khvajeh Do Kuh, he gestures to a place where 180 of his men died fighting the Taliban. All I see is brown dirt and men on donkeys leading camels along the road. Nothing of the war, death, exile, and victory that have shaped the man sitting in the front seat. There is an emotional landscape here I cannot see.

As we approach the village, the men and boys are lined up in a perfect row a hundred yards long, waiting to greet Dostum. The general gets out of the car and goes down the line, trying to embrace and talk to each person, but it is getting dark. The crowd of men follows Dostum into his father’s compound.

In a tiny, sparse room are his father, Dostum’s former teacher, and a village elder. The old men are frail, with deeply lined faces. The teacher giggles, his white beard shaking with joy. Dostum’s father talks to his son as though he were a child, telling him that he and the teacher have been praying for his success. They reach out to shake his hand, to embrace him. The men in the room try to act formally, but as Dostum starts to leave, some begin to cry. An old man yells, “God bless you. We are alive thanks to you.” As Dostum stands on the porch, looking at the place of his birth, he chokes up.

He takes me to the hilltop above the village. It’s a high, lonely place. When war first came to Afghanistan, two decades ago, he built his first stronghold here to guard the village. Dostum points to the fresh dirt of new graves in the cemetery. “The men who first defended this post with me are all dead now. The new graves belong to those who were fighting terrorists.” He is silhouetted against the slate-blue sky, the long tails of his silver turban whipping in the wind.

For a brief moment, the general stands triumphant, the conquering hero, the bring-er of peace, the warlord who has ended war in the north—and, therefore, perhaps eliminated his own reason for being. As he leans into the Afghan wind, the light falls, and a moment in history fades.

The first monument to CIA officer Mike Spann, the first casualty in the war on terror was erected by General Dostum. Here Spann interviews Lindh but Lindh remains silent. Moments later Mike would be murdered by prisoners.

Dostum must now change his focus from fighting to rebuilding his country. (Within a week, he will be named deputy minister of defense for the new interim government of Afghanistan.) Now, on most mornings, Dostum emerges from his house, squinting into a crowd of turbaned men waiting for an audience. They sit patiently for hours, clutching tiny pieces of paper, seeking his aid. Dostum’s meetings do not end until well after midnight.

Not long before I’m to leave, Dostum asks for help with a letter of condolence to the widow of Mike Spann. The task inspires him to try to express his feelings about the past two months. He confesses that he had worried at first how the Americans would handle Afghan warfare: “It was cold; the food was bad. The bread we ate was half-mixed with dirt. I wondered if they could adapt to these circumstances. I have been to America and know the quality of life they enjoy. To my surprise, these men felt at home.”

And more than that: The Afghan warlord and his tiny band of American soldiers had clearly formed a bond that only men who have been through combat can understand. “I now have a friend named Mark,” Dostum says, referring to the Green Beret captain. “I feel he is my brother. He is so sincere; whenever I see him, I feel joy.” He pauses for a moment, lost in reflection. “I asked for a few Americans,” he says finally. “They brought with them the courage of a whole army.”

Down the road at the Regulators’ make-shift barracks, a call comes over the Motorola: “Pack your shit.” The men quickly gather their gear, as they have so many times before. Within hours, they are gone.

Afterword.

The team was under orders not to talk to journalists. Since I was a guest of General Dostum it was a little difficult for the men to avoid me. After a while we soon got along. There were some deep unresolved internal conflicts because of the death of Mike Spann and why they over their protests had been sent to Kunduz. After our time in country, I became friends with the men and defended them when they were accused of war crimes by the media. A bizarre story called “The Convoy of Death” surfaced and painted Dostum and the team in a negative light. After days of killing as many Taliban as they could they were accused of murdering prisoners in shipping containers. Newsweek, The New York Times and other outlets insisted that eyewitness had seen American soldiers laughing and shooting into containers. Prisoners were so hot that they had to lick the sweat off each other one man said. An NGO insisted that thousands of corpses were dumped at a graveyard called Dasht-i-Leili outside of Shiberghan but refused to actual exhume them. It didn’t seem to matter that there was no actual evidence. An odd case of a lack of evidence being brought forward as the evidence. This scandal would tarnish General Dostum’s very real accomplishment of being America’s most aggressive and stalwart ally against the Taliban and al Qaeda.

The mystery of missing prisoners was never matched up to the careful medical records kept of each al Qaeda and Taliban detainee kept by doctors and local NGO’s. ©Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

The problem is that the the Convoy of Death story is false. I was at the prison in Sheberghan when they unloaded the trucks and watched the Red Cross medics count the dead and note the wounded. The wholesale conversion of talibs to the government side during the Kunduz surrender had created confusion in how many Taliban existed in the North. Was it ten thousand, five thousand, The actual number was around 3,500 who surrendered, another 460 al Qaeda showed up at the gates of Mazar and around 250 – 300 died of their wounds, disease or suffocation during transport in the frigid weather. I know because I counted the dead bodies. The only mystery was the lack of interest in the NGO, governments and media in investigating the facts.

Although I spoke out on behalf of the team the media, didn’t publish my eyewitness photos and testimony because it would go against a narrative that a Pashtun backed by a European-backed central government must rule Kabul, not a coalition of regional leaders.We did not want the Taliban voting themselves back into power, yet we restrained the grass roots power of the ethnic minorities. Sidelined, and in exile in Turkey, In 2009, Dostum was begged by President Karzai to come back from exile to reelect him and again in 2014 Dostum engineered the victory of President Ghani….only to go back into exile. To this day the war continues and Dostum as First Vice President remains a staunch ally of America.

Back in 2002 and 2003 the film and book industry were not interested in books or movies about Afghanistan. Our war had been big footed by Iraq. When SFC Bill Bennett invited me over to join the team SCUD hunting before the war he did not like that war. Later on he had a dark premonition. “I don’t think I will make it through this one” he wrote me in an email just hours before he was gunned down on a raid in Ramadi. It was September 12, 2003. Bill and the team were wearing armor decorated with my logo when he died. I was asked to sit on the same row as the team during his funeral. An event and a man I will never forget. There is a need to never forget the sacrifices men make in war. We must honor their truth not the fiction that creates more wars.

In Hollywood I was asked to join meetings during which actors and producers pitched the story, read half a dozen books in which the idea of John Wayne like cavalry charges and Dostum’s ogre like cruelty were fictionalized into cartoons. The men know their story and I wrote it down. Some were angry then, some had been through enough wars to see what was coming.

They are currently enjoying some well earned recognition now that the film 12 Strong has been released but again, the film is not anywhere close to the truth. We will never end wars if we don’t understand how to win them. A story of how 12 Americans and a Afghan warlord won the war on terror, if only for a brief time still remains to be told.

© 2018 Robert Young Pelton, all rights reserved

ryp@comebackalive.com