by Robert Young Pelton

In a humid, 88-degree summer swelter, Erik Prince pulls up on his Cannondale mountain bike drenched in sweat but unwinded. Dressed in a cheap white polo shirt, the 41-year-old ex–Navy SEAL, ex–CIA assassination point man, and avid adventure racer has just pedaled over to meet me from his self-described redneck mansion, a low-key brick affair a few miles away in North Virginia horse country, where he has been raising his seven school-age children. The next day, Prince will board a flight from Dulles International Airport, heading off to begin a new life in Abu Dhabi, the capital of the United Arab Emirates — a nation, some have been quick to note, that lacks an extradition policy with the United States.

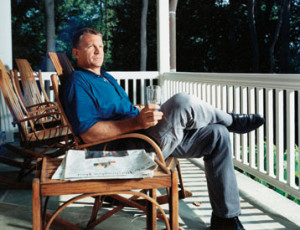

Today he needs to pack, and he wants to be with his kids, but he also needs to talk. He has some things he needs to get off his chest, some things he wants everyone to know. He greets me politely, takes a seat, and proceeds to remove the batteries from his cell phone — “It’s too easy to eavesdrop these days,” he says. Then he checks his Breitling watch and shoots me the impatient look his business associates know only too well: Let’s get on with it.

In phone calls leading up to our meeting, Prince was angry — furious, even — that he and Blackwater, the company he built from a ramshackle shooting range into a $1.5 billion one-stop shop for war-zone services to the Pentagon, U.S. State Department, and the CIA, continue to endure what he views as a ceaseless and politically motivated “proctological exam.” The company will go on (it recently won a fresh $100 million contract from the CIA), but Prince, seething with betrayal, has had enough: “I’m done. It’s all sold or shut down. I’m getting out of the government contracting business.”

Since the clumsy February 2009 rebranding effort in which Blackwater was renamed Xe (pronounced “zee”), both current and former executives, Prince says, get deposed regularly by investigators from at least six federal agencies, including Congress, the Pentagon, the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives, and even the Department of Agriculture. They’re looking for dirt to support what Prince dismisses as “baseless” accusations that run the gamut from negligence, racial discrimination, prostitution, wrongful death, murder, and the smuggling of weapons into Iraq in dog-food containers. One witness, Howard Lowry, who traveled to Iraq frequently between 2003 and 2009, testified on September 10 that Blackwater contractors had him procure steroids and other drugs for them, and that he was invited to weekly all-night parties in Baghdad’s al-Hamra hotel.

“One of the suites would be absolutely packed with gentlemen running around with either no clothes on, no shirt on,” he said in a court document that was leaked to the media almost instantly. “It was like a frat party gone wild. There was cocaine all on the tables. There were blocks of hash, and you could smell it in the air.” Lowry gave his testimony as part of a 2008 lawsuit brought by two former Blackwater employees, who allege that Blackwater sent the bill for hookers and strippers to Uncle Sam and that Prince benefited from this fraud. Prince says there’s no merit to the charges: “When we found knucklehead behavior, we fired them.”

Though Prince stepped down as CEO of Xe on March 2, 2009, the IRS, he claims, is auditing his personal income taxes, all while press reports and blogs call him a “war profiteer,” “right-wing crusader,” and “mercenary” (a term he despises), and imply that he is fleeing the country to escape justice.

But if he is on the run, his evasion skills need help. Xe/Blackwater recently agreed to pay the Feds a $42 million fine for a series of niggling violations; when we meet, Prince is one week away from a seven-hour deposition (with an attorney who followed him to Abu Dhabi) for a lawsuit financed by the New York–based Center for Constitutional Rights. It’s a matter of public record that he’s sold off or closed many of the 30-plus companies that he created to handle discreet contracts from the government between 2004 and 2009. Meanwhile, he still fumes that he was outed as a covert CIA operative in August 2009, a leak he blames on his Democratic enemies in Congress and newly appointed CIA director Leon Panetta’s incompetence.

“Look at the stink they raised when a low-level agent like Valerie Plame was revealed,” he says. “What happened to me was worse,” he adds, going on to call the leak criminal. His cover blown, he tells me he has nothing left to hide.

If there is a short version to where it all went wrong, Prince’s curt response sums it up: “Nisour happened.” On September 16, 2007, Blackwater guards were sent to clear the way for a U.S. State Department convoy and ended up opening fire on a busy traffic circle, killing 17 Iraqis. Because of a special order established in 2004 that exempted Blackwater contractors from Iraqi law, the five Blackwater employees who shot up the square were indicted in the U.S. for voluntary manslaughter; Prince, looking like Ollie North’s boyish nephew, appeared before Congress soon after the bloodbath to explain the expanding and deadly role of private contractors in Iraq. (On December 31, 2009, a U.S. district judge dismissed all the manslaughter charges because the case against the Blackwater guards had been improperly built on testimony given in exchange for immunity.) Many of the victims of Nisour Square and their families accepted State Department–approved payouts for their silence, but Prince says a suit may be refiled in North Carolina. “It won’t go anywhere,” he adds.

At the time of Nisour, Prince and Blackwater had already been engaged in a legal battle for nearly three years with the families of four men who were brutally murdered in Fallujah in 2004 while in Blackwater’s employ. The attorneys for the families undertook a negative PR campaign against Blackwater. Because he is wealthy and held sole propriety of the company, Prince himself made an ideal target for their smears.

Although Prince says he’s saddened by the deaths of the 33 Blackwater men killed on the job (he teared up about it at a private going-away reception the previous day), he chalks up the loss of life not to his or Blackwater’s hubris, but simply to war, and men doing dangerous work in dangerous places. At every turn, he points out, Blackwater followed the orders of its client — U.S. government officials — who, he says, often put his men in harm’s way. His one regret? “I wish we had never worked for the Department of State. They’re not worth it.”

Prince is not a chatty fella, and as he downs a second bottle of spring water, I have to ask him the same question multiple times to get him to answer — like starting a car with a dead battery. You can tell by his manner and the length of his replies what he wants to talk about (his dad) and what he doesn’t (the sensational accusations against him that speculate on his plans).

While he allows that taking up residence in Abu Dhabi will “make it harder for the jackals to get my money,” he tells me that his move to the Persian Gulf isn’t about avoiding the courts, but rather about being home for dinner with his kids. No, he’s serious: His real motive for leaving the country, he assures me, is that he can get to Abu Dhabi quickly from his undisclosed new work in “the energy field” — a future that has his detractors wondering what’s scarier: Erik Prince running security for the State Department and spying for the CIA or Erik Prince freelancing in the Middle East.

If Prince seems like a man in a perpetual hurry, it’s because he is. For one thing, the men in the Prince family have a genetic predisposition to early death from heart disease. Prince’s grandfather Peter died of a heart attack at age 36, his uncle at 60, and his own father nearly died of one when Erik was three. “My dad was scared, but focused,” he recalls. “He was a tugboat that pulled a lot of boats behind him.”

Born in 1969 to Edgar and Elsa Prince, Erik was their only son (he has three sisters) and grew up in Holland, Michigan, a conservative Dutch-immigrant enclave that could be the setting for a Norman Rockwell painting. Like many in business and politics, Prince wears his family’s hard climb to success like a badge of honor. Edgar started his own company in 1965, and during Erik’s early childhood, the family of six lived in a heavily mortgaged house about a third the size of his mother’s current estate on Michigan’s Lake Macatawa.

At the time of Edgar’s near-fatal heart attack, he and his business partners had just developed their breakthrough product: a lighted sun visor with a mirror, first introduced in the 1973 Cadillac. More innovations followed, including a built-in garage-door opener, digital compass, and thermometer, which made Edgar Prince rich. What impressed Detroit the most was that Prince Industries invested its own money in R&D and often successfully predicted the little things that made the difference to the car-buying public.

Prince soaked up his dad’s business philosophy around the dinner table. He also absorbed his father’s focus on family. “My dad insisted on being home for all of my sporting events,” he says. “He even kept a fleet of aircraft so his sales guys could be home from meetings in time for dinner.”

From an early age, Erik liked to push his luck. As early as 12, he tested himself by sailing alone on Lake Michigan, and he ran a trap line in the cold Michigan winters. As a teen he was a cold-water diver for the sheriff’s department (to find drowned snowmobilers) and a volunteer firefighter while attending Hillsdale College, a privately funded libertarian school in southern Michigan.

As he built his fortune, Prince’s father became a prime mover in the Christian evangelical movement, his mother overseeing donations to James Dobson’s Focus on the Family and other conservative political action groups. The relationships his father developed through his philanthropy not only informed Erik’s worldview but also became important to his business prospects later. In 1990 Edgar secured Erik a low-level internship in the White House, but Prince soon quit for a much more exciting opportunity to intern for California Congressman Dana Rohrabacher, Reagan’s former speechwriter and an ex–freedom fighter against the Soviets in Afghanistan.

Rohrabacher recalls that Prince, a “bright, driven young man,” volunteered to search for a mass grave in Nicaragua to expose Marxist-turned-president Daniel Ortega as a killer. “I went down there with this other guy from Dana’s office,” Prince says. “It was the first time I had to shake a surveillance tail, from the Sandinistas.” He was 21, eight days shy of his first wedding, and thrilling to his first taste of international intrigue. “We found a mass grave: bones sticking out of the ground, hands tied with wire at the wrists.”

More adventure awaited him. Prince’s initial goal was to become a Navy carrier pilot, but in the era of Tailhook, he was turned off by the frat-house antics at the naval academy. Switching to the Navy SEALs, he found his calling. But first he had to pass Basic Underwater Demolition School — one of the toughest selections in the military.

“The cool thing about the SEAL teams is that the only difference between enlisted men and officers is that the officer has a white stripe on his helmet,” Prince says. He found in the SEALs both an outlet for his intensity and a credo for his entrepreneurial drive. “The sea is the most difficult environment to operate in — on land you have a few hours to sort out your problem, but if you have problems in the water, you’re not going to live unless you sort them out in seconds.”

In 1993 Prince joined SEAL Team 8, based out of Norfolk, Virginia. “I figured I would be a SEAL for the next 10 to 12 years. There wasn’t much going on then. The invasion of Haiti was a non-event. It was mostly training, training, and more training. Had I stayed longer, I would have seen action, but things changed at home.”

On March 2, 1995, Edgar Prince collapsed from another heart attack and died. Later that same year, Prince’s wife, pregnant with their second child, received a cancer diagnosis. Prince finished out his fifth year as a SEAL but returned to civilian life sooner than he’d planned. “You roll with the punches,” he says stoically.

For the next eight years, his wife struggled with cancer, until she passed away in 2003. He refuses to elaborate but allows that “the saddest moment of my life was her funeral.” He was 34.

When the Prince Group sold in 1996, one year after Edgar’s death, it garnered $1.35 billion. Though split between several of his dad’s business partners, numerous employee stockholders, his mother, three siblings, and him, the windfall still set Prince up for life. “My SEAL friend suggested that maybe I should invest the money, kick back, and live off the interest,” Prince says, in a rare moment of reflection. “In hindsight that wasn’t such bad advice.” Instead, he created the ultimate boys club in a North Carolina swamp.

Prince’s original plan, created with help from veteran Navy SEAL Al Clark, was to build the dream training facility — a place all his buddies from Norfolk could use. “We needed 3,000 acres to make it safe,” Prince recalls. After searching for a location for six months, he ended up paying $900,000 for 3,100 acres (or about $300 an acre) in Moyock, North Carolina. The swampy, tannin-stained “black water” and the bears on the property inspired both the name and the famous bear-paw logo. By the time the Blackwater Lodge and Training Center officially opened on May 15, 1998, the footprint had doubled in size, to 6,000 acres, and Prince was into it for $6.5 million. Over the next few years, he would invite a number of influential members of the military, FBI, local law enforcement, and even the CIA to visit and play “Blackwater.”

At first, locals didn’t pay the range or Prince much notice. “To the degree that [Prince] was thought of, it was as this patriotic guy who had built this Hail Mary facility to help the SEALs, and who probably hoped to break even,” recalls Jay Price, staff writer for Raleigh’s The News & Observer, who tracked Blackwater’s rise to prominence. “The big contracts weren’t on the horizon, not even a glimmer, and I don’t think anyone in their right mind was thinking of him as a greedy military-industrial profiteer.… Maybe as a kid from money who was looking around to see what his role in life would be.” Prince could have spent the next few decades in eternal adolescence, impressing and entertaining his shooting friends at the “Lodge” and staying out of the limelight, but 9/11 would change that.

Before 2001 the term contractors referred to retired agency and special operations vets who knew each other by reputation or service. The small pool of retired “Tier One” operators, usually middle-aged men with smeared tattoos and worn SF or SEAL rings, were discreetly hired and signed up for overseas gigs with few questions asked and little to no public divulgence.

Shortly after 9/11, Cofer Black, the former CIA head of Counter Terrorism, put out the word to hire more than a hundred “shooters” for Afghanistan. The CIA would “sheep dip” (reassign under false cover) active operators and activate “green badgers” (cleared agency contractors) for the CIA Special Activities Division. Once the agency moved from using small mobile paramilitary operations in Afghanistan to larger, fixed installations, it quickly realized that it needed a more robust type of protection: The tiny old boy’s network was soon tapped out. That’s when the CIA turned to Prince and his clubhouse.

In the spring of 2002, Buzzy Krongard, the number three at the agency, presented Prince with Blackwater’s first “mission”: Could Prince provide 20 men with top-secret clearances and have them on a plane to Kabul within a few days? Their job in Afghanistan would be to protect the CIA headquarters and one remote OGA base, in Shkin, supporting the hunt for Bin Laden. Friends were called, and Prince quickly had his team. A six-month, $5.4 million contract was rushed through as “sole source, urgent and compelling need.” What’s more, Prince assigned himself to be part of the group so he could make sure his customer was being well served.

Once in Afghanistan, Prince couldn’t wait to get back to the States: He realized right away that he could make millions more providing security teams than he could running a shooting range. His new “private military company” would be to the Pentagon as FedEx was to the Postal Service. And his sales pitch to CIA bureaucrats was about as sophisticated as his $17 haircut. “We did it cheaper and better,” he boasts. Blackwater was paying each man $550 a day and billing the agency $1,500 all in. It was hard for Prince to lose money.

Then came Iraq. By spring of 2003, an old-fashioned land war had given way to a robust State Department and CIA political mission. Hundreds of young U.S. diplomats and case officers, many of them straight out of college, were posted to Iraq to shape a new nation. The Bush administration initially expected the same jubilant response from liberated Iraqis that they had seen in Afghanistan, but they would be proved wrong. Newly assigned viceroy Paul Bremer, tasked by President Bush with creating a transitional government (the Coalition Provisional Authority), needed a dramatically different form of protection, and so did all the

diplomats. Normally, the government is responsible for its own security, but it simply didn’t have the staff for such a high-risk personal-protection detail overseas. From the government’s point of view, contracting for this protection also outsourced the political risk in the event of a screwup or fatality. The contractor, not the client, would take the heat — and the bullets.

In the fall of 2003, Blackwater was awarded the $27.7 million “Bremer Detail,” a Department of Defense contract that essentially created a Frankenstein brigade of highly visible hired guns. Blackwater provided the security to the Iraq Survey Group (the ISG was the CIA group looking for proof of weapons of mass destruction), allowing the ISG to travel anywhere in the country with the guarantee of safety.

By the time I first visited Blackwater, in July 2004, to lead a course on how to think like a terrorist for a bunch of special-forces types who were about to be deployed to Afghanistan, the Lodge was well on its way to becoming a networking center for U.S. and foreign special operations and anyone else hoping to be recruited for security work in Iraq and Afghanistan. The place reeked of Prince’s weakness for Boy’s Own derring-do — from the hunting lodge/summer camp/club house–type decor to the main office, which featured trophy animals and gun-enthusiast magazines.

Outside on the many shooting ranges, brass glittered in the gravel; the popping of bullets was ever present, as were the sounds of screeching tires and explosions from the driving track. Fifty-caliber rounds fired from the sniper range echoed off the portable buildings with a metallic shriek. Well-muscled men in tan T-shirts and crushed ball caps methodically cleaned their M4s and pistols outside the chow hall. Inside, a long line of plaques and mementos from police and special operations groups decorated the entry to the offices. Off in the distance were aircraft fuselages, Navy ship towers, and a village built from Conex containers. Longtime Blackwater president Gary Jackson even had a desk made out of armored steel. Jackson and Prince were proud of the tactics they had developed to operate in Iraq — Prince still is.

“We were using low-profile, armored indigenous vehicles with teams of two and four,” Prince says, explaining that he chose the “low profile” look to protect the ISG. That look consisted of operators wearing local dress moving in beat-up yet armored taxis, with weapons held below the windows. “You can’t shoot at what you can’t see,” he says. Blackwater was suddenly guarding arguably the most hated man in the most violent country on Earth — and Prince rose to the challenge. “Not one State Department employee was killed while we were protecting them,” he says.

While Prince’s success may have been partly the result of his aggressive approach, it made some of his own executives nervous. “Erik decided to become a lightning rod and then [attach it] to his ass,” says Mike Rush, another ex–Navy SEAL and former Blackwater vice-president, of Prince’s business manner. “Erik would walk up and down the corridors of Langley and the Pentagon telling everyone how fucked up they were and how they should run the war,” he continues. “That’s nice…but we had to do business with those people.”

Prince’s “sell first, figure it out later” style injected massive stress into his rapidly expanding venture. Everyone remembers him as impatient. Prince’s own stance on those early days: “You hire people, they don’t work out, you move on.” In the scramble to keep contracts manned, Blackwater trained, hired, and rotated thousands of men. The men generally had little time for their bureaucratic State Department counterparts, and the natural tension between them became fertile ground for payback when the media and lawyers came looking for sources with a score to settle with Prince. But between 2003 and 2007, Prince had his own agenda and didn’t focus on petty squabbles.

In 2002, a few short months after 9/11, the CIA had turned him down for a job when he applied to be part of its Clandestine Services, specifically the Special Activities Division of the agency. The CIA, he says, told him he didn’t have enough “hard skills.” So, two years later, in December 2004, he hired the CIA — bringing in Cofer Black following 28 years of service with the agency. Prince installed the former CIA exec as Blackwater’s “chief breacher” — the man who blows in doors on a SEAL team.

As Blackwater grew, so did Prince’s ambitions. Indulging his lifelong love of aviation, he began assembling a small air force of smaller cargo planes, helicopters, and even large transports (including a Boeing 767) for either a Dulles-to-Baghdad run or the rendition of terror suspects, depending on whom you believe.

He also hatched a plan to vertically integrate all these assets to form a self-sufficient army of 1,740 men — an “army in a box” complete with air support, medical and construction outfits, and high-tech weapons that could deploy instead of, say, a United Nations peacekeeping brigade. Registered in Barbados under the name Greystone, this new company was designed to hire foreign employees and operate outside U.S. legal restrictions. “It is more difficult than ever for your country to successfully protect its interests against diverse and complicated threats in today’s grey world,” Greystone’s brochure stated. Prince even pitched then Secretary of State Colin Powell a version of this: a battalion-size humanitarian force that could provide “relief with teeth” in the Darfur region of Sudan. To Powell and his advisors, Prince’s gunned-up proposal was as politically acceptable as calling a nuclear strike on an orphanage.

Meanwhile, as if Prince didn’t have enough going on, the CIA finally accepted him for its NOC program. As a “non-official cover operative,” he was given a polygraph and an operational code name, and only his handler knew his true identity from his “201” personnel file. Prince volunteered to find terrorist targets for “capture or kill.” Twice he was able to come through, but authorities in Washington never gave the green light.

Blackwater was supposed to be the grease in the wheels of regime change in Iraq, but there was soon serious friction. Numerous troubling events that had been buried in action reports came to light: Blackwater was suffering from its success and spreading itself too thin.

In the violent fall of 2004, I spent an unrestricted month covering Blackwater teams running the charred route between the Green Zone and Baghdad International Airport. The daily 15-minute thrill ride often included close calls, angry Iraqis, sniper attacks, car bombs — enough near-death experiences to last a lifetime. I was able to see the service that our government was buying, and while I also took taxis and private cars without incident, I found Blackwater’s teams aggressive but professional.

But when I returned to Baghdad in 2006, at least one contractor complained that Blackwater had become a “flat-out sloppy fucking operation,” and the men I knew apologized to me for the “roid-rager” who told me to “get the fuck out of here” when he heard I was media.

The press soon brought Blackwater’s most egregious acts to the attention of the public: dead Iraqis, a crashed plane, crushed vehicles, a drunken shooting of a vice-president’s security man, media guards gunned down, and much more. On the CIA side, “big-boy rules” were in effect. These rules are a tacit code among covert operatives that states that there are no rules until you break one — by, say, appearing before Congress on every television on Earth. Prince’s mission to find terrorists fizzled and then died under the new administration. Finally, with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in power (as a senator, she had introduced legislation to put the kibosh on private contractors), Blackwater ran out of oxygen. So Prince, ever the SEAL, quickly assessed, adjusted, and moved on.

America won’t get an apology from Prince, because in his view, he did what he had to do and, crucially, what his government asked him to do. Yes, Blackwater has paid off victims of its violence, but only under the direct advice of its client, the U.S. State Department. When Prince had to get equipment in-country to keep his clients and his people safe, he did. When his staff racked up 300 counts of violations while following client orders, he simply ate the fine. It’s like another popular slogan SEALs use during training: Pain is just weakness leaving the body. Now Prince is leaving the pain and taking himself out of range.

Financially, Prince may yet come out ahead. His quick estimates are that his failed self-

financed ventures, like armored trucks and airships, burned about $100 million. Toss in another $50 to $60 million in legal fees (last year alone he spent $24 million) and another $42 million in government fines, and then subtract the net-after-tax income from the billion and a half in estimated government contract revenue: How much did he make? “The rule of thumb is that you plan for 15 percent and are happy if you make 10,” he explains. “I have enough to live comfortably. I’m a multimillionaire, but with way less now. I am almost embarrassed I didn’t make more money.”

Prince won’t provide details on his future other than that he won’t be accepting government customers. “The media tends to screw up my plans,” he says. Still, it’s no secret Blackwater’s up for grabs. As of press time, a letter of intent had been drafted regarding its imminent sale. Reconciled but not pleased with this outcome, he pauses for a moment, searching awkwardly for a way to sum up his payback. He thinks he has it: “Atlas Shrugged.” He means Ayn Rand’s novel in which defiant engineer John Galt protests stifling bureaucracy by convincing other leaders to bring society and government to the brink of collapse. It’s clear that Prince identifies with Galt. It’s also clear that he will not abandon his dreams.

Sitting inside Prince’s toy-cluttered Suburban hours before his flight to Abu Dhabi, I press him once more to define himself against the caricature many have of him — somewhere closer to evil than Iron Man’s Tony Stark. At first he is reluctant, even embarrassed by the question. Then he tells me, “I try to live by the Parable of the Talents” — Matthew’s story in the Bible about the chastising of a timid servant who buries his master’s money out of fear, and the praising of an industrious servant who increases his master’s money tenfold. But he shifts again; Talents isn’t exactly right.

“I don’t plan to meet my maker tanned, fit, and rested,” Prince says, at last. “I intend to be tired, battered, and bruised.”

—

The Golden Age for Contractors & Mercenaries

Blackwater/Xe may have been dropped from the State Department’s Worldwide Personal Protective Services contract, but Xe founder Erik Prince’s vision for his industry is being realized on a scale that even he could not have imagined — with firms such as DynCorp International and Triple Canopy (both now located in Virginia) racing to fill the contracts denied Xe. How big are we talking? Despite being an outspoken critic of private contractors during her 2008 campaign for president, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton will soon preside over a private army in Iraq that dwarfs that of the Bush era. Here is a look at the current Obama administration’s security plans for Iraq.

7,000 HIRED GUNS

On August 2, 2010, President Obama announced: “Our commitment in Iraq is changing from a military effort led by our troops to a civilian effort led by our diplomats.” To keep those diplomats safe, however, the State Department plans on doubling — to roughly 7,000 — the number of private security guards and low-paid foreign mercenaries assigned to U.S. personnel and locations.

WORLD’s LARGEST EMBASSY

Approximately the size of Vatican City and costing $592 million, the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad is among the largest and most expensive in the world, even though it was built with cheap, imported labor. A bunkerlike complex of 21 buildings, it spreads over 104 acres and houses 835 employees. Private guards maintain the complex and other facilities in Basra, Erbil, Hillah, Kirkuk, and Tallil.

2,500 ARMORED SUVs and 50 MRAPS

To enable our diplomats and nation-builders to move safely around Iraq, the U.S. Embassy has ordered up a fleet of between 2,500 and 3,200 armored sport utility vehicles at a cost of approximately $150,000 each and has asked the departing U.S. military forces to leave it 50 MRAPs — 28,000- to 42,000-pound trucks built to withstand massive roadside IED explosions.

PRIVATE AIR FORCE

Twenty-five Black Hawk helicopters and a small number of fixed-wing aircraft and air-support crews will also be used to transport embassy staff between locations. Blackwater pioneered the concept of using “Little Birds” with two snipers to protect SUV convoys (and as rescue or escape vehicles). DynCorp International will replace Blackwater in providing this air support.

This article was originally published on Tuesday, November 30, 2010 in Men’s Journal.